NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD 1968

When Panic Blossomed and the Dead Remembered Us: Visceral Nightmares and the Birth of the Flesh-Eating Apocalypse in Romero’s Living Dead

I’ll never forget the first time I saw Night of the Living Dead—mainly because I spent half the movie peeking through my fingers, clutching my Milk Duds in one hand and my dignity in the other. My older brother, ever the sadist (or maybe just a budding cinephile, no, it was typical older brother mischief), and his pal, decided I was finally old enough to be initiated into the world of raw horror! Not just late night Chiller Theater, or Universal horrors, or afternoon 50s sci-fi giant rubber bugs and evil aliens horror, and he dragged me to the theater with his equally mischievous pal.

There I was, wedged between them, squirming in my seat while the smell of popcorn and impending doom I hadn’t even conceived existed yet, filled the air. Every time I tried to shield my eyes, my brother’s hand would clamp over mine, prying my fingers apart.

I’d never seen anything like it. When that first ghoul came lumbering toward Barbra and Johnny in the graveyard, right after she’d laid down the flowers, I thought I’d walked in late and missed an entire setup, when it jumped to Johnny’s “They’re coming to get you, Barbraaa!” I thought it was supposed to be a joke, but I didn’t get the irony or the gravity—I was too busy trying not to lose my Pepsi and my composure. Suddenly, the terror was so real, so relentless, that I was convinced I’d never sleep again. Honestly, I was more worried about surviving the next ninety minutes than surviving the zombie apocalypse. That night in the theater, I realized Night of the Living Dead was unlike any monster movie I’d ever seen. It terrified me to the core, rewired my idea of what horror could be, and left me with a lingering suspicion that the real monsters might be sitting right next to me, elbowing me to keep my eyes open. There’s so much to unpack in this film—its social commentary, its revolutionary gore, and all the gory details in all their gory detail- even in black-and white— practically begs for a full-blown autopsy. So stay tuned, drive-in friends, because I’m about to dig deep into Romero’s masterpiece, and I promise not to flinch… much.

There’s a certain mad genius to George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead—a film that didn’t just birth a new kind of monster, but detonated a cultural bomb whose shockwaves still rattle the bones of horror cinema. Romero, a Pittsburgh native cutting his teeth on commercials and the occasional Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood segment, wasn’t the obvious candidate to reinvent the genre. But maybe that’s exactly why he did. Tired of the rubber masks and Gothic castles of old, Romero and his ragtag team at The Latent Image originally wanted to make something raw, immediate, and, above all, terrifyingly real. A more traditional zombie story evolving from Romero’s earlier short film Night of the Flesh Eaters but budget constraints and a healthy dose of creative desperation led Romero and co-writer John Russo to strip their story down to the marrow: flesh-eating ghouls, a farmhouse under siege, and the end of the world as we know it. The Zombies were here! And we became meat!

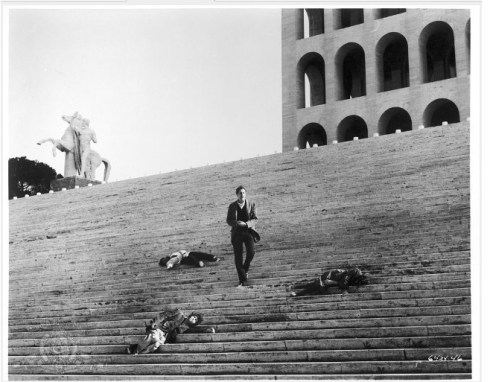

Romero’s inspiration came partly from Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, but where Matheson’s vampires haunted a post-apocalyptic wasteland, Romero wanted to show the world’s collapse in real time, minute by nerve-shredding minute. Matheson’s story would be adapted to the screen as Vincent Price’s visual poetry, The Last Man on Earth 1964, directed by Ubaldo Ragona and Sidney Salkow, which was a meditation on isolation, mortality, and existential despair. It would later be visualized in 1971 as The Omega Man, directed by Boris Sagal and starring Charlton Heston, Anthony Zerbe, and Rosalind Cash.

With a shoestring budget and a Pittsburgh crew, Romero stripped the genre of its Gothic trappings and set his horror in the everyday: a rural farmhouse, a newsreel-black-and-white palette, and a cast of ordinary people whose terror felt uncomfortably real. Romero’s zombies were something new—relentless, cannibalistic, and devoid of any master, serving as a chilling mirror to the living.

He shot the film in and around Pittsburgh, using the condemned farmhouse as the main set—a place so decrepit that the crew sometimes slept there, lacking running water and proper amenities, they bathed in a nearby creek. The black-and-white 35mm film wasn’t an artistic flourish but a necessity. Yet, it gave the movie a newsreel immediacy, as if the apocalypse were unfolding on the evening broadcast. Romero’s guerrilla style—handheld shots in moments of chaos, slow pans for creeping dread, and static frames that felt like visual traps—turned every budgetary limitation into a creative advantage. The lighting is pure chiaroscuro, shadows looming as large as the ghouls themselves, and the grainy texture only heightens the sense of documentary realism.

The sound design is equally unvarnished: instead of a swelling orchestral score, Romero leans on ambient noise, radio static, and the primal thud of drumbeats. The effect is uncomfortably intimate, as if you’re barricaded in that farmhouse with those doomed characters, hearing every groan, every shuffling footstep, every splinter of wood as the dead close in. Trapped in that farmhouse, panic hit me in a visceral wave—my chest tight, breath shallow, every sound from outside like a fist pounding on my nerves. It was a raw, animal fear I’d never felt before, the kind that made my skin prickle and my instincts scream that there was nowhere safe, not even inside my own shaking body in the safety of the musty theater’s seat.

Makeup, handled by Marilyn Eastman and Karl Hardman (who also act in the film), is a masterclass in DIY horror: sunken eyes, mortician’s wax, and enough chocolate syrup to make Bosco a silent partner in the production. The zombies—never called that in the film, only “ghouls”—move with a lurching, sideways menace, their faces as twisted and gnarled as the tree roots. They bore the open petals of rot, wounds blossoming in the silence of death, as they stumbled past. For god’s sake, the one picking the thousand-legger off the tree and eating it is enough to make me wretch.

The cast, largely unknowns and locals, bring a rawness that only adds to the sense of escalating panic. Duane Jones, as Ben, contributed significantly to developing his character and rewrote much of his own dialogue, transforming the intended rougher, more blue-collar truck driver. Jones brought a calm, intelligent, and authoritative presence to the role. From a rough truck driver into a resourceful survivor—the first Black protagonist in American horror, and a casting choice that would become freighted with social and political meaning.

The casting of Duane Jones in the lead role of a horror film- a Black actor- as the level-headed, capable protagonist was groundbreaking. Romero insisted his casting was all about talent, not politics, but in 1968 America, Ben’s fate could not help but echo the country’s violent racial history. A Black man being gunned down by a white posse couldn’t help but resonate. The film’s nihilism—its sense that the real horror is not the monsters outside, but the divisions, paranoia, and violence within—mirrored a country reeling from assassinations, Cold War paranoia, distrust of American institutions, civil unrest, and the Vietnam War.

The film’s final, gut-wrenching moments—Ben surviving the night only to be shot and killed and thrown onto a pyre—evoke images of lynching and the brutal realities of race relations in the U.S.. The stark, documentary-like stills that close the film are eerily reminiscent of civil rights-era photographs, confronting viewers with the inescapable truth of America’s inequalities.

Judith O’Dea’s Barbra, all wide-eyed terror and catatonia, is the audience’s conduit into the nightmare. Karl Hardman and Marilyn Eastman as the bickering Coopers, Keith Wayne and Judith Ridley as doomed young lovers, and Kyra Schon as the sickly, soon-to-be-ghoul Karen—all of them feel like real people, not movie archetypes, which makes their fates that much more wrenching.

The story opens with Barbra and her brother Johnny bickering their way through a cemetery visit—Johnny teasing her with a sing-song:

Johnny: “They’re coming to get you, Barbra!”

Barbra: “Stop it! You’re ignorant!”

Johnny: “They’re coming for you, Barbra! Look, there comes one of them now!”

– right before he’s promptly attacked and killed by the first ghoul, Barbra flees, crashing her car and stumbling into a seemingly abandoned farmhouse.

Enter Ben, who takes charge with a tire iron and a plan: board up the windows, keep the walking dead out, and try not to lose your mind.

The face at the top of the stairs in Night of the Living Dead wasn’t just a face; it was the mask of death itself, peering down with the cold indifference of the grave. For a moment, I was certain my heart had forgotten how to beat. That image haunted the edges of my vision long after the scene had passed, a shock cut, gruesome, ghostly afterimage that refused to fade.

That moment at the top of the stairs is seared into memory—a grotesque vision that put the crack in the veneer that would soon shatter and destroy any lingering sense of safety. The face devoured, the exposed eye, wide and unblinking, seems to follow you, daring you to look away but making it impossible. It was as if the film itself reached out and slapped you awake—no longer just a story, but a visceral shock that turned my stomach and made my skin crawl, a ghastly reminder that in this new world, death is not just an ending, but a spectacle of violation and existential disturbance.

As night falls, the farmhouse becomes a pressure cooker. Ben and Barbra discover the Coopers and a young couple, Tom and Judy, hiding in the basement. Karen, the Coopers’ daughter, is feverish from a bite—a detail that, in true Chekhov’s Gun fashion, will pay off in the most gruesome way possible. Drawing on a classic narrative principle: if a story introduces a significant detail early on, that detail must become important later. Anton Chekhov famously said – From one of the most direct sources, in a letter from 1889, he wrote: ‘One must not put a loaded rifle on the stage if no one is thinking of firing it. It’s wrong to make promises you don’t mean to keep.” Therefore, Karen’s festering wound is significant.

Tensions flare: Harry Cooper wants everyone in the cellar, Ben insists on defending the ground floor.

Ben: “I’m telling you they can’t get IN here!”

Harry Cooper: “And I’m telling you they turned over our car! We were damn lucky to get away at all! Now you’re telling me these things can’t get through a lousy pile of wood?”

They compromise, sort of, but the real enemy is as much inside the house as out. News reports crackle with confusion—radiation from a Venus probe, government incompetence, and the chilling advice that only a blow to the head or fire will stop the ghouls. These lines capture the film’s tension, bleak humor, and iconic status in horror cinema.

Newscaster: All persons who die during this crisis from whatever cause will come back to life to seek human victims, unless their bodies are first disposed of by cremation.

Sheriff McClelland: Yeah, they’re dead. They’re all messed up.”

And then there’s that unforgettable procession: a naked group of ghouls, pale and unashamed, lurching toward the farmhouse with the inevitability of a slow-moving tide. Their bodies, stripped of humanity, shimmer in the moonlight like a grotesque ballet, each step a testament to the film’s refusal to look away from the horror it has conjured.

The survivors try to escape: To get the keys, heroically, Tom and Judy make a break for the truck, but a spilled can of gasoline turns their getaway into a fireball.

Outside, the world burns. When the truck explodes in a blossom of fire, the young couple’s desperate hope is snuffed out in an instant, their love story reduced to cinders and smoke. The ghouls gather around the wreckage as if at a family BBQ, their movements grotesquely communal as they feast on the charred remains—a macabre picnic under the indifferent stars. The sight is both revolting and mesmerizing, a reminder that in Romero’s world, death is not an ending but a ravenous beginning.

Back inside, the barricades begin to fail. The makeshift wooden barriers, tables, and rusty nails groan and splinter under the weight of clawing hands and grasping arms. Fingers snake through every gap, desperate and unrelenting, turning the walls into a living, breathing trap. The farmhouse becomes a ribcage about to shatter, the survivors the last fluttering heartbeats within, as panic and dread pulse in time with each new assault. Every key scene in Night of the Living Dead is a wound that refuses to close—a visceral, unforgettable reminder that fear is not just something you watch, but something that reaches out, grabs hold, and refuses to let go.

Harry Cooper: “Look! You two can do whatever you like! I’m going back down to the cellar, and you’d better decide! ’Cause I’m gonna board up that door, and I’m not going to unlock it again no matter what happens!”

The lights go out. The dead press in, relentless and hungry. Down in the basement, the horror devolves into something even more primal. Karen dies and reanimates, killing her mother with a trowel in a scene that still shocks with its Freudian brutality.

The daughter, once feverish and fragile, becomes a silent predator, her small hands closing around the trowel as she rises from the shadows. The sound of her mother’s screams—raw, animal, echoing off the stone—collides with the wet, sickening rhythm of the attack. It’s a tableau of innocence inverted, a child transformed into the harbinger of her parents’ doom, and the scene leaves you feeling hollowed out, as if the air itself has turned to bloody ice.

Upstairs, Barbra is pulled into the mob by her undead brother Johnny—her fate sealed by the past, quite literally coming back to consume her. Ben, now alone, retreats to the cellar—ironically, the very place Harry insisted was safest—and is forced to shoot the reanimated Coopers. He survives the night, only to be mistaken for a ghoul and shot by a posse of white men the next morning. His body is tossed onto a pyre with the rest of the dead, the film ending not with triumph, but with a bleak, documentary-like montage of burning corpses.

What makes Night of the Living Dead so enduring isn’t just its scares, but its allegorical bite.

This redefinition of the undead didn’t just launch the modern zombie genre; it also created an allegory for a society devouring itself from within. The film’s compressed, real-time narrative—90 minutes of escalating dread—captures the precise moment when history falls apart, when the old world is swallowed whole and nothing familiar remains.

The ghouls are more than monsters; they’re the past come back to devour the present, the mistakes of history clawing their way out of the grave. They are us.

The farmhouse, besieged on all sides, becomes a microcosm of a society collapsing in on itself—cooperation frays, fear triumphs, and the center cannot hold. Night of the Living Dead subverted horror conventions by refusing to offer hope or catharsis. The hero dies, the group fractures, and the world is left in ruins—a nihilistic tone that shocked audiences and critics alike, but which has since become a hallmark of the genre.

George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead revolutionized horror cinema on both a technical and thematic level, forever altering not just what audiences feared but how those fears reflected the world around them. Before Romero’s zombies in cinema, they were tethered to voodoo folklore and colonial anxieties—a far cry from the flesh-eating, apocalyptic ghouls that would soon shamble across America’s collective nightmares, or eventually sprinting, ferocious and relentless as in 28 Days Later 2002.

Romero’s film didn’t just change horror; it changed the way we see ourselves in the dark. Its influence is everywhere: in the flesh-eating zombies that now populate our nightmares, in the social commentary that pulses beneath the genre’s surface, and in the knowledge that sometimes, the scariest monsters are the ones who look just like us. Night of the Living Dead taught horror to speak to the world’s wounds. It is a film that refuses to die—forever shambling forward, hungry for new generations to discover its terrible, beautiful truth.

DAWN OF THE DEAD 1978

George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead 1978 begins not with hope but collapse. WGON-TV in Philadelphia is in chaos: emergency broadcasts warn of reanimated corpses devouring the living while society crumbles. Traffic reporter Stephen Andrews (David Emge) and producer Fran Parker (Gaylen Ross) flee via helicopter, joined by disillusioned SWAT officers Peter Washington (Ken Foree) and Roger DeMarco (Scott Reiniger). Their aerial escape reveals a nation unravelling—cities burn, rural enclaves fortify, and the dead shamble en masse. Romero’s camera lingers on this apocalypse with documentary starkness, framing highways as graveyards and suburbs as battlegrounds. This opening isn’t just a setup; it’s a requiem for modernity, where institutions fail and humanity’s fragility is laid bare.

The film’s pivot occurs when the quartet discovers the Monroeville Mall—a cathedral of consumerism shimmering in the Pennsylvania wilderness. They land, clear its undead, and barricade themselves inside. At first, it’s paradise: Fran models fur coats, Roger races motorcycles through department stores, and Peter savors the absurd luxury of a world where you can take anything you want. Romero contrasts these moments of hedonism with eerie wide shots of zombies clustered at escalators and glass storefronts, their hollow stares mirroring pre-apocalypse shoppers. The mall’s fluorescent glow and muzak score (by Goblin in international cuts) create a surreal dissonance—life as a discount-daydream, punctuated by the groans of the damned outside. This isn’t accidental; Romero, inspired by visits to Monroeville Mall, weaponizes the setting. The mall is both sanctuary and prison, a glittering trap where survival mutates into complacency.

Stephen: “Why do they come here?”Peter: “Some kind of instinct. Memory, of what they used to do. This was an important place in their lives.”

Later, Peter also says: “They’re us, that’s all, when there’s no more room in hell, the dead will walk the earth.”

Romero’s social critique sharpens as the survivors’ utopia warps Roger’s reckless bravado leads to a zombie bite, and his agonizing death—followed by reanimation and Peter’s mercy killing—shatters the group’s illusion of control. Months pass in montage: Fran’s pregnancy advances, Stephen obsessively guards “their” domain, and Peter smashes tennis balls in silent despair. The mall’s abundance becomes oppressive; its frozen food, designer clothes, and jewelry now symbolize emptiness. Romero intercuts this with decaying emergency broadcasts, emphasizing global collapse. When a nomadic biker gang storms the mall, shattering barricades and unleashing zombies, the film erupts into carnage. Stephen, consumed by possessive rage, ambushes the invaders—a choice that gets him bitten and devoured. In the climax, a reanimated Stephen leads zombies to their hidden quarters, forcing Peter and Fran to flee by helicopter as they lift off, low on fuel and flanked by undead.

Visually, Dawn of the Dead revolutionized horror. Cinematographer Michael Gornick used handheld shots for chaos (e.g., the SWAT raid’s claustrophobic violence), static frames for dread, and saturated colors to heighten the mall’s artifice. Tom Savini’s practical effects—decapitations, disembowelments, and the iconic helicopter-propeller decapitation—elevated gore into visceral art.

“I saw some pretty horrible stuff… I guess Vietnam was a real lesson in anatomy. This is the reason why my work looks so visceral and authentic. I am the only special effects man to have seen the real thing!” (Tom Savini)

His goal was always to create effects that felt both shocking and credible. Savini has also spoken about the playful, almost “magic trick” nature of his work with Romero:

“You are fooling people into believing in the illusion. I guess me and Romero wanted to be magicians of murder. If you see our names on the cinema billboard then you know you’re in for a really great magic show that will make you laugh but may also give you nightmares.”

Romero’s zombies aren’t just monsters; they’re darkly comic metaphors. Their lumbering through boutiques and food courts literalizes consumerism’s mindless ritual. It’s a visual dripping with class contempt.

The film’s racial politics also simmer beneath: the opening tenement raid, where police brutalize Black and Latino residents hoarding undead loved ones, parallels real-world systemic oppression. Peter, a Black protagonist wielding agency in a white-dominated genre, embodies resilience against a system that cannibalizes the marginalized.

Forty-six years later, Dawn’s allegory remains razor-sharp. Romero framed consumerism as a pandemic—one where malls are temples where people worship without thought, and humans, like zombies, define themselves by acquisition. The film’s genius lies in balancing satire with sincerity: Fran’s rejection of Stephen’s proposal underscores the collapse of meaning in a material world. When Peter and Fran vanish into an uncertain dawn, Romero offers no triumph, only ambiguity. Their helicopter, dwarfed by the undead-infested mall, becomes a symbol of precarious survival in a world where the true horror isn’t the dead, but what the living become when stripped of illusion. Dawn of the Dead endures not just as a gore milestone, but as a mirror to capitalism’s ravenous soul—a reminder that in the mall of life, we risk becoming lost souls and the walking dead long before we die.