1950s horror sci-fi is where paranoia met pure creativity and gave birth to some of the most enduring legends of genre cinema. From swamp creatures to giant bugs! These films aren’t just charming relics and campy curiosities of a cheesier past; they’re a cultural echo chamber of mid-century imagination, packed with the decade’s tangled fears and wild dreams, the kind that turned B-movie budgets into unforgettable, iconic nightmares.

Jack Arnold’s Creature from the Black Lagoon 1954 embodies the seductive mystery of the unknown, a restless ripple in the waters from the murky depths of classic horror. It is a synthesis of primal fear and awe of human and waterborne beast, blending horror, adventure, and myth into one unforgettable creature feature.

The Gill-Man stands as a potent symbol of nature’s raw, untamable force, and the era’s fascination with scientific discovery teetering on the edge of hubris. Whether it intended to do so or not, Creature from the Black Lagoon isn’t shy about exploring themes of colonial arrogance and extractivism. The film touches on the harsh reality of greed, the tragic cost of intrusion, the taking, destroying, and plundering of Indigenous lands and their resources. But, after surfacing all that underlying social commentary about intrusion, otherness, and the follies of poking at nature’s mysteries, this Universal gem delivers one hell of a Finomenon, a Gill-faced legend who swims straight past mere monster status and splashes down forever in the pop-culture deep end.

What really stays with me about Gill-Man and why I adore him as much as I do, is what a sympathetic hero he is, how he captures the tragic cost of human arrogance; he’s an innocent force of nature caught in the unsettling squeeze between man’s devouring hunger and the tightening grip of primal threat. making him less a monster to be feared and more a silent victim of a world that refuses to understand him.

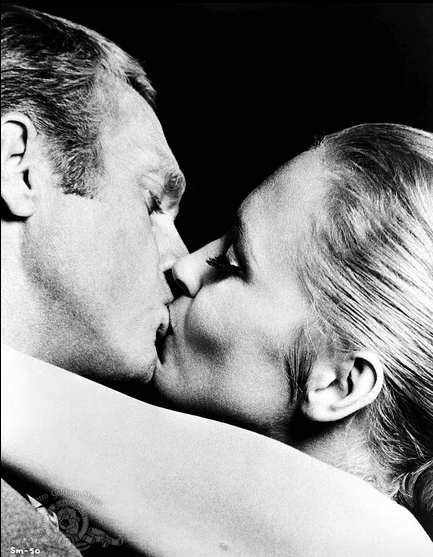

Unlike typical ‘50s monsters who are villains by design, the Gill-Man feels like a displaced guardian, more casualty than culprit, more pawn than predator, more beast to Julie Adams’ beauty struggling to survive against relentless exploitation. His haunting presence resonates as a poignant reminder of what is lost when curiosity crosses into invasion, making him less a creature to be feared and more a symbol of nature’s misunderstood and mistreated majesty.

Behind this iconic figure lies a lesser-known story: Milicent Patrick, a brilliant artist whose visionary design shaped the creature’s unforgettable silhouette but whose name was largely erased from the credits. The Gill-Man drifts between worlds: horror, myth, and adventure, beckoning us into those shadowy waters where curiosity, fear, and Julie Adams, and we swim side by side.

Beware of the Blob! It creeps, and leaps, and glides and slides across the floor.

Meanwhile, The Blob 1958 subverts the monster formula with its amorphous, insatiable menace, a vibrant metaphor for Cold War fears, communal hysteria, and invasive threats, all captured in saturated Technicolor that oozes with 1950s Americana charm. Its legacy lies as much in its cultural resonance as in its simple, relentless terror. It all begins when a mysterious meteorite crashes near a sleepy small town, unleashing a steady wave of gelatinous terror that devours everything and everyone in its unstoppable path. What starts as a curious spark when an inquisitive old man pokes the meteorite with a stick, unknowingly unleashing the gooey alien, quickly turns into a suffocating nightmare of disbelief, chaos, panic, and ceaseless consumption.

Steve McQueen in The Blob is the quintessential small-town hero, young and determined for his first leading role. McQueen’s Steve Andrews is the one who sees the growing threat no one else believes at first, the guy rallying his friends and town to face an unstoppable, all-consuming gooey menace (“Watch it wiggle, see it jiggle- There’s always room for Jell-O”). It’s a role that’s less about flashy acting and more about earnest resilience, the classic cool kid standing up when it counts, even if it means nobody’s listening at first. This film gave McQueen a platform to start building the charisma that would later crown him the King of Cool. The Blob may ooze menace on screen, but its bouncy title tune by legendary maestro of pop music, Burt Bacharach and Mack David, makes it sound like the friendliest monster ever to shimmy into a drive-in! The song was a long way off from Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head!

In Jack Arnold’s Tarantula 1955, the monstrous isn’t small or subtle; it’s a gigantic spider bred from scientific ambition and atomic age anxiety, crawling right over the decade’s conflicted national psyche, balancing tension with just enough camp to keep things thrilling in that charmingly low-fi 1950s way.

Though I applaud its inventive visual effects, especially Arnold’s clever use of live-action spider shots blending seamlessly with rear projection and miniature sets, which created an unexpectedly convincing giant menace despite the budget’s constraints. Professor Gerald Deemer cooks up an experimental nutrient meant to solve world hunger by sparking runaway growth. No need for a Spoiler alert: the formula, far from perfect, turns the lab animals from cute to colossal in no time flat. Things really spiral when Deemer’s assistant, looking less like himself by the day thanks to the serum, accidentally sets loose a tarantula that’s swollen to monstrous proportions. Cue chaos, screaming, and a whole lot of running for your life!

John Agar stars as the town’s Dr. Matt Hastings, the steadfast hero racing against time to stop the giant menace, while Mara Corday’s Stephanie “Steve” Clayton isn’t your classic genre damsel; she’s a scientist who rolls up her sleeves and steps into the fray with brains to match the beauty. Then there’s Leo G. Carroll – Professor Gerald Deemer, the scientist whose own twisted, albeit altruistic, ambition and misdirected humanity pushes the nightmare into motion, 8-legging its way through the desert. Together, their uneasy alliance spins the story into a cautionary yet wildly entertaining tale of pioneering zeal gone awry, where science tries to save but winds up threatening the day.

Keep Watching the Skies! Science Fiction Cinema of the 1950s: The Year is 1955

Finally, The Fly 1958 delivers a tragic, grotesque transformation narrative that probes deeper into the psychological and ethical terrain. The human-fly hybrid became an unforgettable icon of mutation and loss of control, reflecting fears of scientific hubris and bodily horror (famously fueled David Cronenberg’s fascination with body horror, leading to his striking remake released on August 15, 1986) with a grim inevitability. The Fly buzzes with a nightmarishly fascinating tale of tragic metamorphosis, where scientific ambition goes wildly wrong, infecting both body and soul. David Hedison stars as the obsessed scientist André Delambre, whose experiment to teleport himself merges disastrously with a hapless fly, turning him into a grotesque hybrid that’s as heartbreaking as it is horrifying. Patricia Owens plays his devoted wife, Helene, caught up in the nightmare, suspended in the fragile balance of love and loss. Just to add to The Fly’s ‘50s allure, Vincent Price, as always, shines as François Delambre, the relentless brother piecing together the horrifying puzzle of his sibling’s unimaginable fate. This film digs a bit deeper for a’50s creature features, mixing mutation mayhem with a serious dose of psychological and ethical dread, all with a wink of dark humor that keeps you both horrified and oddly sympathetic.

And just when you think things can’t get any weirder, we get the iconic finale: François Delambre waves a rock over a spider’s web, where the miniature fly with brother André’s head and arm is desperately screaming, “Help me! Help me!” with a monstrous spider inching closer for the kill. The moment with his famously tiny, high-pitched, and almost childlike voice is a desperate squeak trapped inside the miniature human-fly hybrid’s small frame. It’s a fragile, trembling plea, full of raw, heartbreaking terror that somehow manages to skitter between eerily pathetic and horrifically farcical.

With perfect deadpan timing, Herbert Marshall as the police inspector crushes them both, sealing the fate of one of horror’s most tragically bizarre hybrids. Nobody’s quite ready to believe a man with a fly’s head was really killed in the hydraulic press. François tells the inspector who came to arrest Patricia Owens for murder, “You killed a fly with a human head, she killed a human with a fly head. If she murdered, so did you!”

So François takes it upon himself to gently erase the impossible evidence, not just to grant his brother a merciful release, but to spare the world from a nightmare fiction too surreal to believe. It’s a hilariously grim send-off that somehow manages to be both absurd and deeply unsettling. Add that scene to the list of iconic moments in genre cinema!

Together, these films show how the ’50s handled the darker side of progress, mixing clever artistry and practical effects with just the right amount of schlock and spectacle, which makes revisiting them a lovingly nostalgic thrill. They remain vibrant testaments to a time when moviemakers turned societal unease and real-world worries into unforgettable monsters that keep on menacing and tickling us today.