THE WOLF MAN 1941

“Even a man who is pure in heart and says his prayers by night may become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms and the autumn moon is bright.”

There is, quite simply, no way I could possibly hope to contain what The Wolf Man means to me, in all its unsettling lyricism, invented folklore, and shadowy intensity, within the reach of a single essay. To try would be to count every mist swirling through those haunted Welsh woods, or to trace each echo of Curt Siodmak’s poetic fatalism as it seeps beneath the celluloid, marking not just Larry Talbot but the history of horror itself. This is a story that transcends the beast-and-victim paradigm, turning the Universal monster mythos inward, to a place where every man (or woman) —“even those who are pure in heart”—finds the possibility of darkness flowing inextricably through their nature. It is beloved because it feels, on some haunted level, true. And when Lon Chaney Jr. first shambles across the moor on the balls of his hairy feet as Larry, awkward, yearning, resigned to his fate as only Chaney could be, we find a vulnerability so raw and so human that the legend ceases to be a legend at all.

Something else I’ll explore in my in-depth walk through the Welsh woods at The Last Drive In is how classic horror films like The Wolf Man and, for example, Lewton’s Cat People with his production techniques that gave him the new tools in his quest to expand classical horror’s parameters, would navigate the contours of sexuality with a deft subtlety, threading repressed desires and overt fears through their narratives. As Gregory William Mank observes, the movie horrors of the 1940s “took a sly twisty route to the libido and subconscious of its audience” when exploring themes of latent longing and hidden identity beneath the surface of monstrous transformation and psychological terror.

Instead, it becomes a parable of the soul’s double shadow, irresistible precisely because It cannot be reduced to a simple collection of scenes or a fleeting glance at the performances; this film resonates at the very heart of our love for classic storytelling, its living, breathing soul escaping any attempt at neat summary, demanding instead to be felt in every shift of Larry Talbot’s tragic trasnformation and glow of the eeire full moon’s powerful light.

I will have to lavish much more time and loving attention upon this film very soon, returning to the fog, the myth, and the indelible heartbreak that Universal, Siodmak, Waggner, and above all Chaney summoned for all eternity. Until then, this will remain only an overture, a single howl in the woods, echoing all that still calls for closer devotion.

Universal’s The Wolf Man (1941) remains one of the beating hearts of the legendary monsters of classic horror, a work that not only cemented the studio’s iconic status but also set the tone for generations of monster cinema. The film’s script, penned by Curt Siodmak, is as much a reflection of its creator’s experience as it is a fantasy of Gothic terror. Siodmak, a German émigré haunted by the trauma of fleeing Nazi Germany, poured his anxieties about fate, persecution, and transformation into the story of Larry Talbot, an American-educated man returning to his Welsh ancestral home, played by Lon Chaney Jr—the character and the actor; dual souls branded by a dark star of inevitable sorrow and tragedy.

Curt Siodmak’s legacy as a writer is one of profound influence on the horror and science fiction genres, which helped shape mid-20th-century genre cinema. His work is marked by his deft blending of myth, psychology, and existential dread. Best known for creating the werewolf mythos in The Wolf Man (1941), Siodmak infused his scripts with a deep sense of tragedy and inevitability, exploring themes of fate and transformation that transcended typical monster narratives. His notable screenplays aside from The Wolf Man include Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man 1943, a sequel which expanded the Universal monster universe, and The Devil Bat (1940). Siodmak’s work helped solidify Universal’s classic monster cycle, introducing a lyrical and human dimension to monsters. He also wrote The Invisible Man Returns (1940), I Walked with a Zombie (1943), and The Beast with Five Fingers (1946), showcasing his range within horror’s Gothic and psychological realms.

Branching into science fiction, Siodmak also penned Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956) and adapted his own seminal novel Donovan’s Brain multiple times for the screen, solidifying his reputation as a visionary storyteller who merged cutting-edge science with speculative terror. Beyond writing, he directed a handful of films, including Bride of the Gorilla (1951) and The Magnetic Monster (1953), demonstrating versatility not only as a screenwriter but also as a filmmaker. His work reveals a captivating mix of literary heart and genre-bending creativity, something that still ripples through horror and sci-fi cinema today.

Lon Chaney Jr. was indeed the son of the legendary silent film actor Lon Chaney, known as “The Man of a Thousand Faces,” but he was not originally known by the stage name “Lon Chaney Jr.” at birth; his given name was Creighton Tull Chaney. After his father’s death, he adopted the stage name Lon Chaney Jr. around 1935 as a career move to capitalize on his father’s legacy, which helped establish his career in Hollywood but also placed him in the shadow of a titan. Over time, especially starting with The Wolf Man, he was billed simply as Lon Chaney, dropping the “Jr.” The name change was more a strategic marketing decision by studios than a nickname he was commonly referred to by early on. Despite this, he made the name his own through his memorable and emotionally compelling performances, especially as Larry Talbot, the tragic Wolf Man, establishing himself as a major figure in Universal’s horror pantheon in his own right rather than just “the son of Lon Chaney.”

Chaney became forever identified with the tormented Larry, a role demanding empathy as much as physical transformation. As Larry, he is awkward yet affable, his longing for acceptance and love quickly poisoned by his fateful encounter with Bela Lugosi’s fortune-teller, whose own lycanthropic curse is only hinted at with brief, powerful screen time. Lugosi, the iconic star of Dracula, brings an eerie sadness even in his cameo as Bela, the doomed Romani who consents to his own tragic fate when he recognizes the pentagram of death.

The director George Waggner had a journeyman’s touch, guiding the film with a sure sense of atmosphere, pacing, and an eye for dramatic transformation. Working alongside cinematographer Joseph A. Valentine, he created a landscape of perpetual dusk, where early mist swirls around atmospheric rural and village settings, hauntingly dark twisted woods, and the brooding interiors of the Talbot estate. Valentine’s cinematography is instrumental: the film is bathed in fogs that never quite reveal the contours of the land or its lurking evils, and the low, slanting light throws elongated shadows that seem poised to engulf Larry at every moment to emphasize Larry’s haunted, dual nature and his looming fate. Valentine later shot Hitchcock’s Rope (1948), known for its visual innovation.

From Man to Monster: The Fierce Alchemy Behind Jack Pierce’s Wolf Man

The transformation scenes in The Wolf Man are a masterclass in classical cinematic metamorphosis, painted with a haunting brush of both dread and melancholy. Jack Pierce’s unsettling makeup work blossoms in gradual, mesmerizing stages as Lon Chaney Jr.’s Larry succumbs to the curse: the slow, spectral fade from human to beast.

One of the most unforgettable signatures of The Wolf Man is the groundbreaking cinematic façade and transformation effects by Pierce, which required hours of work daily and achieved a haunting new realism for the time. Pierce’s alchemical artistry was less about mold and mask and more about breathing wild life into flesh and hair, painstakingly gluing tufts of yak hair strand by strand, then singeing them with a hot iron to forge untamed fur that seemed to grow like creeping tangles across Chaney’s face. Far from a mere disguise, Pierce’s technique was a grueling ritual of transformation, sculpting the werewolf’s visage with layers of cotton, collodion, and that iconic rubber nose, each element breathing a raw, animalistic pulse beneath the surface. The skin coarsened, as if summoned from beneath a wild thicket of fur, sprouting untamed like creeping vines across his face, bristling with fibers, spreading with a brutal, living texture: a wild garden sprung not from earth but from human skin, framing a leathery, primal snout that marked the beast within.

Despite its brilliance, the makeup process tested the endurance and patience of Lon Chaney Jr., who reportedly resented the long, uncomfortable hours spent in Pierce’s chair, yet it was this collaboration that ushered in a breakthrough in horror makeup effects, blending detailed realism with fantastical transformation. Pierce, known for his stubborn craftsmanship and old-world techniques, insisted on building every brow and detail from scratch daily, rarely using molds to maintain the uniqueness and tactile depth of his designs. The painstaking hours in which Chaney bore Pierce’s unforgiving magic, sometimes feeling the searing heat of the curling iron on his cheek, made each frame a testament to old Hollywood’s blend of craftsmanship and torment, creating a monstrous look both terrifying and tragic, utterly inseparable from the actor’s own weary humanity.

The film’s practical dissolves, saving the full horror of the Wolf Man’s visage for a devastating reveal, cutting softly between overlapping images, capture hands retreating into monstrous claws, his skin charged with latent fury, and feet and ankles reshaping into the toe-walking stance characteristic of lupine grace before our eyes. There is an eerie poetry in the way Larry begins to walk on the balls of his feet, a deliberate subversion of human gait that gives his creature form an unsettling, predatory elegance; every step betrays the monstrous nature trying to reclaim its dominion. This gait, unnatural yet fluid, conveys the silent tragedy of his condition: a man stripped of his humanity, condemned to a primal rhythm of loss and rage.

Pierce quietly shaped the soul behind the Wolf Man’s mask. His face carries a raw, aching humanity, a portrait of pain and sorrow, of mournful eloquence, a restless blend of feral instinct and fragile soul, a vulnerable ferocity, and just maybe a reflection of the sorrow we somehow recognize in ourselves. It’s this shared ache that binds us to him. It’s why I’m drawn to helping feral cats. Their ‘humanity’ or more aptly, cats’ (and dogs) sentience, soulfulness, honesty, heart, wild nature and spirit call to us.

Among the cast, Claude Rains stands towering as Sir John Talbot, the rational, emotionally distant father whose skepticism and sternness are shaded by regret and anguish. Evelyn Ankers plays Gwen Conliffe, who brings warmth and intelligence, at once strong-willed and compassionate, divided by duty and genuine affection for Larry.

Lon Chaney Jr. and Evelyn Ankers are remembered as one of classic horror’s most intriguing on-screen pairings, their chemistry in The Wolf Man (1941) palpable and emotionally charged. Despite their compelling collaboration in six Universal films, including The Wolf Man, The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942), Son of Dracula (1943), North to the Klondike (1942), Weird Woman (1944), and The Frozen Ghost (1945), their off-screen relationship was famously strained. Ankers reportedly found Chaney to be difficult or brusque at times, occasionally perceiving him as a bully, while Chaney gave Ankers the nickname “Shankers,” which hinted at a complicated back-and-forth, a mix of annoyance and familiarity. While there’s no clear drama or outright hostility on record, they kept things professional enough to deliver solid performances, even if things weren’t always smooth between them.

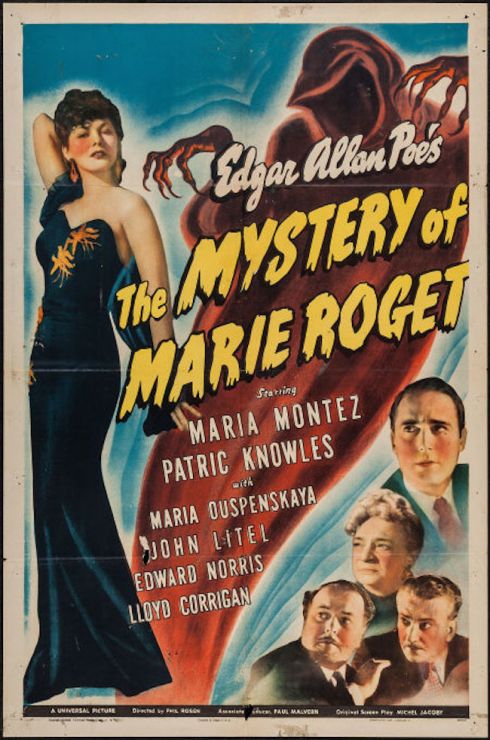

Ralph Bellamy plays Colonel Paul Montford, the local chief constable who embodies authority, and Patric Knowles plays Frank Andrews, a gamekeeper and Gwen’s fiancé. Both represent parochial suspicion and the protective, watchful, and somewhat skeptical public face of the grieving and fearful community around Larry Talbot and the mysterious werewolf attacks.

Fay Helm is the innocent Jenny, whose fateful palm reading seals her doom early in the tale. Maria Ouspenskaya, as Maleva, is unforgettable: she is all finally honed gravity and sorrow, mother to Bela and soothsayer to the newly cursed. Her delivery of the film’s famous saying, “Even a man who is pure in heart and says his prayers by night…,” reverberates as oracle, poetry, and curse all at once. No one but Maria Ouspenskaya could carry that line with such quiet grace and soul, her voice a steady murmur of integrity and solemn truth.

The film unwinds in visual and dramatic episodes that are now canonical: Larry’s awkward attempts to reconnect with his father after the death of his brother, his courtship of Gwen, and the trio’s night walk to the Romani camp that ends in violence. After Bela reads Jenny’s palm and sees the pentagram, terror erupts in the woods as a wolf attacks. Larry’s desperate defense leaves him bitten; he later learns he has killed not a beast, but Bela himself. Thus begins his spiral of paranoia and remorse. Doubts from Sir John and the villagers, the growing suspicion as evidence piles up, and the mounting internal pressure, all are punctuated by fog-wrapped evenings, floating camera movements, and the Wolf Man’s prowling. And, there is the tragic climax, with Sir John using Larry’s own silver-headed cane to fell his monstrous son while Gwen and Maleva watch in horror and pity.

In the muted mist of ancient Llanwelly, Wales, The Wolf Man begins with a poignant son’s return: Larry Talbot, played with aching vulnerability by Lon Chaney Jr., comes home, seeking reconciliation with his distant father, Sir John Talbot after the tragic death of his brother. The estate, shrouded in fog and silence, is the stage where fate waits patiently. A fleeting reunion with Sir John speaks of unresolved grief and cold distance, setting a tone of brooding melancholy.

The first meeting between Larry and Gwen Conliffe in a quaint antique shop where he buys a cane that is crowned with a silver wolf’s head, flickers with the gentle glow of innocence and burgeoning affection, set against the ominous backdrop of fate’s cruel hand.

This moment carries with it symbolic weight: This fateful acquisition is no mere accessory but a foreshadowing talisman, taking a mundane step into the realm of the mythical. The cane’s silver top both marks Larry’s new identity and offers a wary defense against the curse’s grip, a breakable yet brave charmstick. Larry is quietly drawn to the strength it embodies, even though it cannot ultimately protect him —in a world about to darken irrevocably. The wolf’s snarling head on the cane is an ominous reflection of the beast lurking beneath Larry’s skin, a beast he will soon struggle to contain.

Gwen’s spirited presence balances Larry’s brooding vulnerability; her quick smile and steady gaze are a brief respite from the shadow encroaching on him. Their interaction hums with a subtle spark that is equal parts infatuation and protective care, marked not by flamboyant passion but the slow, tentative unfolding of affection that makes Larry’s later descent all the more heartrending, laying the groundwork for a tragedy that feels intimate, personal, and deeply sorrowful.

Larry’s tentative courtship of Gwen feels like a fragile light pushing through gathering shadows. Their meeting blossoms with understated warmth, though the weight of fate hangs quietly between them. Not long after, accompanied by Gwen and her spirited friend Jenny (Fay Helm), Larry ventures to a Romani camp that feels like a threshold to the uncanny. Here, the mysterious and foreboding Bela (Bela Lugosi) reads Jenny’s palm and, seeing the pentagram’s cruel mark, signals a grim warning of what’s to come.

The night suddenly erupts into raw fury when a wolf, snarling and spectral, attacks Jenny. Larry steps in, striking down the beast with his new wolf-headed cane, a chilling emblem of his curse just beginning to take hold.

By morning, Larry sees the cost clearly: he discovers the wolf was none other than the ill-fated Bela, and he has been marked by a wound that speaks of something supernatural. Larry’s wound mysteriously heals overnight, casting doubt and suspicion among the villagers and local authorities, including Colonel Montford and Dr. Lloyd (Warren William). Larry sets out to convince others of his plight, but is shunned.

After the bodies of Bela and another villager are found, and Larry’s silver cane is discovered at the scene, suspicion quickly falls on Larry. The fact that he and Gwen weren’t with Jenny when she was attacked only fuels the gossip, with whispers hinting at something scandalous. Despite Gwen’s fiancé Frank Andrews doing his best to defend her reputation, the rumors just won’t die down, and Larry and Gwen find themselves increasingly alienated from the community.

The story emerges piece by piece through suspicion and isolation as Larry’s once steady world begins to crack. His father’s cold disbelief, the village’s whispered gossip, and Larry’s own rising paranoia hang over him like a shadow of loneliness.

In search of answers, Larry encounters the stoic Romani matriarch, Maleva, whose somber knowledge carries the weight of tragic inevitability. She reveals the curse binding Larry to the lycanthropic fate foretold by “even a man pure at heart.”

The scene where Larry Talbot first meets Maleva is hauntingly significant and steeped in a palpable sense of fate and sorrow. When Larry encounters her, she is a solemn figure whose grim knowledge casts long shadows over his future. Maleva approaches with a quiet authority, her voice both commanding and compassionate as she reveals the terrible truth that Larry, having been bitten by the werewolf, is now bound to the same curse that claimed her son Bela. The exchange is suffuse with ritualistic importance and Maleva’s prophetic warnings, her offering of a protective charm, and the atmosphere thick with inevitability. Through her, the film pierces the veil between superstition and reality, underscoring the tragic destiny that Larry is powerless to escape. Ouspenskaya’s presence is like an ancient echo, a living embodiment of sorrow and tragic acceptance.

The transformation sequences unfold as slow, agonizing poetry, hands morphing, feet reshaping into lupine claws, Chaney’s haunted movements shifting to the primal gait of the creature stalking the creepy, people-less marshy woods. Larry’s terror intensifies as he senses the irrevocable loss of his humanity. The full moon, a spectral sentinel, claims his nights as he becomes both the hunter and the hunted.

The chilling progression of Larry’s curse unfolds chronologically: first, he transforms and kills a villager, then he is trapped and rescued by Maleva’s incantation. Haunted by the knowledge that he will next attack Gwen, whose hand he now sees marked by the fatal pentagram, Larry confesses all to his father. Sir John, ever the rationalist, binds Larry in a chair to prove his son is suffering from delusion, keeping the silver cane as a safeguard. But when Larry transforms and escapes, chaos erupts.

In the heartbreaking climax, Larry, now fully transformed as the Wolf Man, attacks Gwen in the foggy woods and is ultimately brought down by Sir John, wielding the silver-headed cane, a symbol of human judgment and supernatural justice, but who does not yet realize the beast is his own son. Maleva arrives, intoning her elegy, her haunting lament that echoes over the scene as the wolf’s death unveils in backward-surging, Larry’s broken human form once more, a final testament to the price of the curse.

Larry’s desperate plea for mercy from a world that has turned against him ends with his execution at the hands of his own father, while the vengeful townsfolk close in, their presence looming at the fringes of the tragedy. Amid the uncertainty of Larry’s curse, a fatal irony emerges; his story, shrouded in fog-laden landscapes and shadowy silhouettes, leaves only confusion and fear in its wake.

This fluid journey cries and growls through mist, moonlight, and heartbreak; it is less a mere monster story than a mournful elegy to the human soul’s frailty, a tale where every shadow holds a mirror, and every howl is an echo of loneliness unspoken.

The Wolf Man includes many compelling scenes that chart Larry’s transformation, both physical and emotional, a haunting odyssey from man to monster, marked by moments of unsettling beauty, creeping threat, and heart-wrenching loss, all delivered with stunning visual poetry and unforgettable performances.

Universal’s The Wolf Man was not just entertainment; it crystallized horror’s capacity for emotional complexity. The film established tropes that would define werewolf stories for generations: the use of silver as a weapon, the pentagram as a mark of the victim, and the curse passed by bite. The Wolf Man forged a tragic monster, one whose most extraordinary victim is himself, and this mythic treatment set it apart from Universal’s previous giants, Frankenstein’s creature and the undead Gothic aristocrat, Dracula, by rooting it in personal guilt, community alienation, and the fear of uncontrollable change. By doing this, it guaranteed Universal’s brand a place in the pantheon of cinematic horror: the brooding sets, expressionist lighting, archetypal monsters, and deeply human stories remain a template imitated but never surpassed, with The Wolf Man as both a brilliant chapter in horror history and a testament to the enduring power of the Universal Monsters.

THE MUMMY 1932

Eternal Longing and the Unseen Bonds: Unraveling the Timeless Enigma of Universal’s The Mummy (1932)

The original The Mummy (1932), is the film that expanded Universal’s archetype of the ancient, restless undead. The film directed by visionary, cinematic pioneer Karl Freund and elegantly captured by cinematographer Charles J. Stumar (Werewolf of London 1935, The Raven 1935) , stands among Universal’s most poetic nightmares, a fusion of supernatural longing, colonial unease, and cinematic innovation.

Freund, whose experience behind the camera as cinematographer on Metropolis and Dracula deeply influenced his visual storytelling, brings weight and subtlety to an archetypal monster that is more haunted lover than shambling mindless killer. The screenplay, shaped by John L. Balderston with contributions from Nina Wilcox Putnam and Richard Schayer, draws inspiration from the fevered headlines around the excavation of Tutankhamun’s tomb, the real-life Mummy’s curse that gripped the headlines in the early 1920s, and the West’s obsession with all things ancient and forbidden.

Boris Karloff, transformed by Jack Pierce’s legendary makeup, is Imhotep—a mummy driven by passion, for whom centuries mean nothing when love and vengeance burn.

The cast is rounded out by Zita Johann (as Helen Grosvenor/Anck-es-en-Amon), David Manners, Edward Van Sloan, and Arthur Byron. Van Sloan plays Dr. Muller in The Mummy (1932), an expert in Egyptology serving as the knowledgeable scholar who helps confront the supernatural threat posed by Imhotep. This character aligns with Van Sloan’s recurring typecast as the wise, heroic professor, similar to his roles in other Universal horror classics, such as Professor Abraham Van Helsing in Tod Browning’s Dracula 1931 and James Whale’s Frankenstein 1931, where he plays Dr. Waldman, the scientist who cautions Colin Clive’s Henry Frankenstein against playing God.

In The Mummy, Boris Karloff plays a dual role, embodying both Imhotep, the ancient, cursed Egyptian priest buried alive for attempting to resurrect his beloved Anck-es-en-Amon, and his modern guise as Ardath Bey, a mysterious Egyptian who infiltrates the contemporary world in pursuit of the reincarnation of his lost love. As Ardath Bey, Karloff is enigmatic, almost hypnotic, a man who wields ancient power quietly but with relentless intent. Both portrayals reflect a singular essence: a tortured soul yearning for reunion beyond the boundaries of mortality. This duality captures the tension between the past and present, the supernatural and the earthly, embodying the film’s threads of Colonialism and cultural imperialism, the persistence of memory and destiny, forbidden knowledge, obsession, and immortality.

Boris Karloff in the role of Imhotep gives a performance that is a haunting blend of tragic dignity, simmering menace, and the burden of centuries. He moves with a slow, unnatural shuffle, with the weight of time wrapped around him, a figure caught between roles of hunter and haunted. His portrayal synthesizes an ancient longing with a brooding intensity, breathing life into his mummy with a poignant mix of sorrow and relentless obsession. Karloff’s Imhotep is less a mindless creature and more a tortured soul, hidden within endless silence and dust, yet driven by an undying love and vengeful will. In one of his most mesmerizing and elegiac roles, he manages to capture the delicate balance between love’s eternal flame and the dark curse of damnation.

Let’s begin with the opening sequences, where the film’s poetic tone is set against the backdrop of Egypt’s sands and the whispers of ancient curses. The scene opens with a sweeping aerial shot, an endless desert of shifting dunes and silent threats, where the camera slowly descends toward the excavation site. This visual intro, bathed in low-key lighting and punctuated by the ominous theme music, immediately evokes the otherworldly tension between the known and the unknowable, the modern and the ancient, representing the expedition in 1921 where the mummy of Imhotep is discovered. The setting was filmed on location at Red Rock Canyon, California, which convincingly doubled for the Egyptian desert, its rocky and sandy terrain providing an authentic backdrop to evoke ancient Egypt.

In the stark, ritual-laden opening the archaeologists on a British expedition, led by Sir Joseph Whemple (Arthur Byron) and his assistant Ralph Norton, digging with their tools striking tombstone and sand pries open the sealed tomb of Imhotep, a high priest punished for sacrilegious passion, buried alive for centuries with the forbidden Scroll of Thoth, forging a moment – that Western tradition has always misunderstood: the reckless human desire to conquer the sacred. This sets the curse in motion. Their’s is the embodiment of the era’s colonial scientific mindset caught between curiosity and the supernatural consequences of disturbing ancient tombs.

As the camera captures this act of defiance, an almost ritualistic violation of eternity, the film delves into layered symbolism. The tomb is more than a burial site; it represents the threshold of forbidden knowledge, a portal through which the past reaches into the present. The scroll, inscribed with hieroglyphs and cursed warnings, whispers of retribution beyond life, hinting at the peril of uncovering truths best left undisturbed. The scene’s richness is underscored by Freund’s use of shadow play, a flickering torchlight that transforms faces into masks of mortal hubris and ancient wrath.

As archaeologists debate science versus superstition, Bramwell Fletcher, who plays Ralph Norton, grows fatally curious.The pivotal moment occurs when Norton, heedless of warnings, unrolls the scroll and recites the incantation aloud. This act, seemingly simple, becomes a poetic defiance, an act of arrogance that awakens the dormant curse. The moment is charged with an ominous silence, broken only by the first whispers of Imhotep’s resurrection.

The resurrection is choreographed with eerie grace: Karloff’s Imhotep, lying down in his tomb, bound and wrapped in his burial linens, slowly unfurls from his eternal dormancy like a cathedral of nightmares emerging from the shadows. The makeup, a masterpiece of pain and patience, emphasizes the ancient’s agony, eyes sunken, face gaunt with centuries’ silence, a vessel filled with longing, revenge, and his tragic burden of release and eternal searching for his forbidden love. This moment, captured in Stumar’s shadow-edged frame, becomes one of horror’s most indelible images: Karloff’s Imhotep shuffles out of legend, stealing both the scroll and Norton’s sanity with a glance that carries the weight of centuries.

When Norton first encounters the awakening mummy, his face becomes a canvas of surreal terror and disbelief that quickly dissolves into hysteria. This moment is one of the most understated yet unnerving sequences in horror cinema. As Norton reads aloud from the Scroll of Thoth, the camera holds tight on his expression, his eyes widen in mounting horror, a numbing shock that tightens his features like the grip of an unseen curse. The mummy’s hand silently appears, seizing the scroll unseen, leaving Norton isolated in an invisible confrontation with death and the ancient unknown. The transformation that follows is hauntingly poetic: Norton’s initial shriek fractures into a manic, hysterical laughter, unearthed madness sprung not from overt spectacle but from the weight of ancient dread pressing down on his fragile psyche. a chilling inversion, his laughter echoing like a death knell, fraught with the collapse of reason under the oppressive silence of the tomb. It is a moment of sublime horror, where the thin veil between the living and the dead frays, captured in Norton’s tortured face, a visage etched by fascination, fear, and the fatal surrender to the curse that has begun its relentless march.

A decade later, Imhotep, reborn as Ardath Bey, steps seamlessly into modern Egypt’s shadows, guiding the next generation of explorers, Sir Joseph’s son, Frank Whemple (David Manners), and Professor Pearson (Leonard Mudie), to rediscover the tomb of Anck-es-en-Amon and helping him to reunite with his lost love. Helen Grosvenor (Zita Johann) is introduced as a young British-Egyptian woman tied to the museum through her connection to Dr. Muller. The treasures are exhumed; Helen, who seems uncannily like the lost princess, is drawn into a web of haunted longing as the ancient love triangle coils toward tragedy.

The scenes move between luminous Egyptian tombs and exquisitely shadowed museum corridors, every setting steeped in colonial anxiety. Moving into the next stretch of the film, it shifts to the orientalist grandeur of Cairo’s museum, where the Egyptian relics reside amidst colonial relics of Western curiosity and conquest. The British characters treat ancient relics as spoils, yet find themselves at the mercy of a power that refuses to be buried by history. Here, Freund’s use of chiaroscuro lighting and sweeping close-ups evokes a spectral beauty, and worlds of myth and history connect. The rediscovery of Imhotep by the modern explorers becomes symbolic of the enduring power of ancient memory, resurfacing from the depths of denial, exposing the hubris of Western imperialism.

As Bey manipulates museum staff to recover the Scroll of Thoth, his magic and malice mount. He uses arcane powers to draw Helen ever closer, inducing her past-life memories as Anck-es-en-Amon. His obsession escalates: Bey kills Sir Joseph to protect the scroll, bewilders Helen with visions of ancient Egypt, and ultimately seeks to murder and mummify her so she will rise again at his side in the afterlife, a horror that fuses death with desire, eternity with regret.

The scene of Helen Grosvenor’s resemblance to the lost princess veers into the realm of poetic tragedy, suggesting that love and obsession are merely two sides of the same ancient coin, centuries-old passions reborn in the modern world. Helen’s increasing vulnerability to past-life memories is painted with eerie lyricism, as Ardath Bey’s rituals and hypnotic influence place her at the center of a struggle not just for survival, but for spiritual possession.

Zita Johann’s Helen Grosvenor, a woman torn between her modern life and ancient memories, enters Imhotep’s orbit, haunted by flashes of past identity and a love that, for Imhotep, has not died. Karloff’s performance, amplified by Jack P. Pierce’s iconic makeup, layer upon layer of collodion, clay, and bandage, endured stoically for hours each shoot, infusing the mummy with sorrow and dignity, and is never merely monstrous; he is driven by passion, regret, and the doomed pursuit of reunion.

Throughout the film, Imhotep’s slow, shuffling approach through shadowy corridors becomes a haunting ballet, a tragic figure embodying longing, regret, and the unbreakable cycle of death and desire. The scene where we learn how Imhotep’s mummy is wrapped, layer upon layer of linen, becomes a poetic metaphor for entrapment and the inescapability of destiny, sealing his fate as both monster and tragic lover.

Ardath Bey’s rites, infused with symbolism, evoke the ancient Egyptian worldview: death as transcendence, yet also as imprisonment. The ritualistic scenes, with their rhythmic incantations and torchlit hieroglyphs, echo the film’s deep-rooted cultural fears, an ancient world that refuses to die, where love, vengeance, and the curse are woven together like the intricate carvings on temple walls. Bey’s magic, such as mesmerism, telepathy, and the curse of death by remote incantation with the burning of tannis leaves during his rituals, serves as a mystical rite that connects the living to the dead, acting as an incense to summon and bridge the ancient spiritual forces. The smoke is symbolic of spiritual awakening and necromantic power, helping to awaken the mummy and fuel its supernatural abilities.

This bridges the realms of forbidden love and lost empire; his efforts to reanimate Anck-es-en-Amon carry the breath of myth and the sting of transgression. More than a monster, Imhotep is a critique: his longing for resurrection, possession, and redemption echoes Western fears of the East and unconscious desires for what lies beyond rational knowledge.

As the story escalates toward its climax, Freund’s direction famously builds the suspense to a fever pitch, the chase across a ruined Egyptian temple, the flickering firelight revealing Imhotep’s gaunt, tormented face, illuminated intermittently by flames, emphasizing his undead and tragic nature, creating a tense atmosphere of supernatural horror during this pivotal sequence. The imagery is both physical and symbolic, illustrating centuries of suffering and obsession.

The moment Helen recalls her past life as Anck-es-en-Amon, a revelation staggered with the pain of reincarnation becomes a poetic invocation of memory over time’s erosion, as she begins to remember her ancient identity and the forbidden love that drove her to be reincarnated. Her voice, trembling with the weight of centuries, ripples through Freund’s framing as if to say my love has lasted longer than the temples of our gods. This lyricism underscores the film’s core theme: the persistence of love and longing through reincarnation and ritual, that death cannot truly sever the bonds forged in ancient Egypt. The Mummy explores how love transcends mortality and how ancient rituals attempt to conquer or preserve the past.

The film’s climax, set against the ruins of a forgotten temple, layers suspense with poetic tragedy, Frank and Dr. Muller pursuing Helen, while Imhotep attempts his final, blasphemous ceremony.

When Imhotep tries to draw Helen (Anck-es-en-Amon) into his doomed existence, he tries to persuade her, saying: “No man ever suffered as I did for you…”, imploring her to understand —not until you are about to pass through the great night of terror and triumph. Until you are ready to “face moments of horror for an eternity of love.”

“I loved you once, but now you belong with the dead! I am Anck-es-en-Amon, but I… I’m somebody else, too! I want to live, even in this strange new world!”

Ardath Bey’s dark ritual attempting to murder Helen and revive her as the reincarnation of his bride Anck-es-en-Amon is foiled only by her desperate invocation of the goddess Isis, a moment of spiritual defiance and protection, breaking the power of the Scroll of Thoth by shattering it and ultimately reducing Imhotep to dust and memory, marking the triumph of sacred power over ancient curses and dark magic.

In these few minutes, the film conflates horror with tragedy, a motif that echoes throughout Universal’s monster canon.

The final scenes, where fire consumes the mummy and the curse is lifted, Imhotep reduced to dust, are imbued with poetic justice. Freund’s use of slow dissolves and stark lighting creates a visual elegy for the fallen priest, and the scale of destruction underscores the futility of defying destiny. The last shot, lingering on Helen’s face as she turns away from the smoldering ruins, the flames purifying, leaves a lingering sense of melancholy, a reminder that some curses, like love, are forever etched into the fabric of history. The lovers are left in a world where ancient curses and colonial ambitions have collided, echoing with both the legendary and the human.

Jack P. Pierce’s makeup artistry achieves a paradoxical effect: imprisoned within linen and prosthetics, Karloff’s face expresses agony, longing, and a sense of being unmoored from time itself. Pierce’s work painstakingly shaped the Gothic iconography of Universal’s monsters, rendering Imhotep as both singular and archetype.

Karloff ANECDOTES:

Karloff said about working with makeup artist Jack Pierce: “He was nothing short of a genius, besides being a lovely man… After a hard day’s shooting, I would spend another six or seven hours with Jack… More than once I wondered if my patience would be rewarded with a contract to play the Monster.”

About the grueling makeup process he endured, Karloff admitted: “I lost track of the number of hours I submitted to the physically draining experience… The application took eight hours, and removal took two hours. It was exhausting but necessary to bring the character to life.”

Karloff’s dedication to the role is captured in how he tolerated discomfort: “The makeup was painful but I was too much of a gentleman to reveal the full extent of the misery I suffered.”

Composer James Dietrich’s orchestration, inflected with haunting stock music and borrowed strains from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, contributes an atmosphere that is both hypnotic and haunted, auditory echoes of lives interrupted, destinies replayed, joins with the script’s rhythmic incantations to suggest a world always teetering between myth and reality. In this way, The Mummy is not just spectacle and monster, but a meditation on longing and loss, possession and release, past and present souls intertwining in the half-light of mortal dreams.

The cultural resonance of The Mummy lies in its layered meaning and the tensions between Western curiosity and ancient mysticism, an interchange fraught with imperial hubris and the desire to possess what should be sacred. Critical scholars have noted how the film subtly critiques colonialism, positioning Imhotep as both a victim of cultural theft and a symbol of the unhealed wounds of history. Freund’s direction, paired with Karloff’s portrayal, a creature at once terrifying and profoundly tragic, transcends simple horror, becoming a meditation on the eternal human quest for love and understanding.

Freund’s direction is full of smooth dissolves, chiaroscuro lighting, and haunting close-ups, which imbue every frame with spectral resonance. Throughout, The Mummy dances between dream and waking, colonialism and myth, science and ancient faith.

In essence, The Mummy (1932) is poetic in its imagery, rich in symbolism, and profound in its exploration of the subconscious fears that haunt us across centuries. It is a film that resonates on a primal level, speaking to the universal themes of desire, betrayal, the unyielding passage of time and the haunting beauty of a story that is as much about the soul’s eternal unrest as it is about monsters from Egyptian tombs.

The Mummy’s impact is enduring. Its influence reaches far beyond Universal’s franchise, still influencing generations of filmmakers and artists drawn to themes of memory, forbidden love, and the fine line between science and superstition. It evokes, with painterly restraint, not simply the terror of the undead but the melancholy of things lost and reclaimed. The film holds steady as a key lens for study on Western appropriation, imperial dreams, and the simultaneous allure and threat of the Other. Freund’s The Mummy is perhaps the purest realization of that, a supernatural tale wrapped in dust, longing, and the persistent whisper of what should remain buried but never does. Freund and Karloff’s masterpiece, with its ancient passions and ritual intensity, digs deeper than graves, lingering in story, psyche, and spirit.

This is your EverLovin’ Joey formally & affectionately known as MonsterGirl, saying — it’s official, this is #150 done and done!

After 150 restless days and nights charting the eerie pulse of classic horror with The Last Drive In, it’s only fitting we drift back to our very first foray—where the terror first stirred in that delicious shadowed threshold between wakefulness and dreams, good old-fashioned smirks, snickers, and screams!

If you want to go tip-toe backward toward the first trembling step, use the link below!

https://thelastdrivein.com/category/monstergirls-150-days-of-classic-horror/

If you’d like the full list of links to each title!