As part of the Barbara Stanwyck Blogathon hosted by The Girl with the White Parasol

THE TWO MRS. CARROLLS (1947)

When I found out that Rachel from The Girl With the White Parasol was hosting a Barbara Stanwyck Blogathon, I chomped at the bit to participate. I love Stanny, pure and simple. She not only changed the way women demonstrated their power in the film, but she’s also gutsy, gorgeous, and persuasive in a very unconventional way.

Barbara Stanwyck, unlike some of her other vice-ridden murderous roles, plays Sally Morton, an archetypal woman in peril, although not as individuated as ‘hysterical’ or pathetic like Leona Stevenson in Anatole Litvak’s Sorry, Wrong Number 1948.

Stanny brought a unique kind of dynamism to the Suspense and noir landscape. Her face, bred with burning spirit and animal coolness, exudes a subtle psychology, ferocious independence, and dramatic intelligence.

The Stanwyck role was originally performed by Elisabeth Bergner in Martin Vale’s stage play. A suspense-thriller that fits within the realm of noir with Gothic tinges of horror. Humphrey Bogart appeared in the classic horror film The Return of Doctor X 1939. Bogart plays the subdued yet sinister malefactor Geoffrey Carroll. He’s a cynical, eccentric, and alienated artist. Stanny plays Sally, the woman he kills his first wife for, poisoning her with glasses of milk, just like in Hitch’s Suspicion 1941.

The Two Mrs. Carrolls is also the second pairing of Humphrey Bogart and Alexis Smith, who plays Cecily Latham, the ‘other woman.’ She first acted opposite Bogie in Conflict 1945, where he played Richard Mason pursuing his wife’s sister, Alexis Smith’s Evelyn Turner.

Produced by Mark Hellinger for Jack Warner and directed by Peter Godfrey (Cry Wolf 1947 also starring Stanny & The Woman in White 1948) The Two Mrs. Carrolls is a woman in peril, female victim story à la Hitchcock.

Stanwyck’s role diverges from some of her more famous female villains, the noir femme fatale who embodies the unacceptable archetype of the sexually aggressive woman. In this film, she plays the more marginalized ‘good woman’ who is worthy of being a wife and often the victim, contrasted by the lustful and conniving femme fatale Cecily (Alexis Smith), who embodies treachery and a freely expressed sexuality.

The film co-stars Nigel Bruce as Dr. Tuttle, Isobel Elsom (Ladies in Retirement 1941, Monsieur Verdoux 1947) as Mrs. Latham Patrick O’Moore as Charles Pennington (Penny), Ann Carter as Beatrice Carroll, Anita Bolster (The Lost Weekend, Scarlet Street 1945) as Christine, the maid, and Barry Bernard as the blackmailing chemist Horace Blagdon. There’s a welter of melodramatic music by Franz Waxman, plenty of Gothic shadows by cinematographer J.Peverell Marley (Hound of the Baskervilles 1939, House of Wax 1953), and gorgeous fashions by Edith Head.

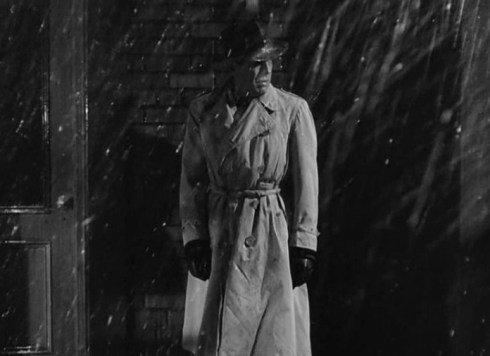

Made in 1945, Warner Bros. most likely held back the release of this film as it was very close to Bogart’s role in Conflict that same year. Bogart, the quintessential scruffy cigarette-smoking everyman equipped with a trench coat, fedora, and gritty sneer, is very capable of playing complex characters with a disturbed pathology of inner turmoil. I think of his role as the controlling and ill-tempered script writer Dixon Steele in Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place 1950 or Captain Queeg in The Cain Mutiny 1954.

In The Two Mrs. Carrolls, Bogart is cast as Geoffrey Carroll, a Bluebeardesque psychotic who first feels driven to paint his muse, the object of his desire, only to feel compelled to destroy her once he’s done exalting her essence using poisoned milk as his method of murder. He is not unlike Vincent Price’s anachronism of a Hudson Valley nobleman driven by an insane need for an heir in Dragonwyck 1946, in an extension of the Bluebeard mythos as he kills his wives who are incapable of giving him sons.

Certain Noir films are the manifestation of psychosis, emerging in the form of the ‘mad artist’, most notablyEdgar Ulmer’s Bluebeard 1944. Franchot Tone was the obsessively deranged sculptor in Siodmak’s underrated film noir Phantom Lady 1944, and Architect Michael Redgrave in Fritz Lang’s incredible depiction of noir psychosis in The Secret Beyond the Door 1947 which had suggestive imagery of a dream-like atmosphere with its overt Freudian fairy tale patterns tied to psychoanalytical interpretations of childhood trauma and sexual significance. Joan Bennett refers to her own ability to purge these ‘repressed poisons’ because she is so chatty and exorcizes her demons by talking too much.

Peter Godfrey’s The Two Mrs. Carrolls and Fritz Lang’s The Secret Beyond the Door 1948 are ideal examples of a leading man portraying creativity and obsessiveness driven to madness. In the former, Barbara Stanwyck plays Sally Morton, who has a whirlwind romance with painter Geoffrey Carroll (Humphrey Bogart), only to learn that he is actually married to an invalid wife. Carroll is desperate to possess Sally, as he claims she has ‘saved’ him so that he can paint again. Before they had met, his work suffered. When Sally finds out that Geoffrey is married, she flees their romantic sojourn, leaving Carroll in a cave, showing dismay and turbulence on his face. Carroll goes to London and sees a chemist, signing a fictitious name. After several glasses of milk, the first Mrs. Carroll is dead, and Sally becomes the second Mrs. Carroll.

Sally becomes his new ‘subject,’ a replacement as the artist’s inspiration and love object. But once the wealthy and decadent tigress Cecily Latham (she wears animal print) aggressively pursues him to paint her and become her lover, Sally’s fate is sealed. Carroll transfers his fixation to his new object, Cecily Latham, played by the gorgeous Alexis Smith (I saw her on Broadway in the 70s. She won a Tony award for her performance in the hit Broadway musical Follies... what a treat!)

The film is an odd and edgy thriller that opens in a pastoral setting in Scotland where Sally and Geoffrey are having a quaint picnic by the lake, while Geoffrey sits upon a rock and sketches her. The initial loveliness and serene atmosphere sets out to misdirect us as a place much like Eden. The couple, we learn, have been dating for two weeks. Everything bears the most ordinary of appearances, as Geoffrey and Sally’s budding romance seems filled with a lighthearted joyfulness in alliance with the surrounding paradisal scenery.

McGregor tells him he’s caught a fish, and Geoffrey yells to him, “Well, from this distance, that takes real talent. Throw that whale back the way I feel today. I don’t want even a fish to be unhappy!”

Geoffrey Carroll tells Sally, “Two weeks of the only real happiness I’ve ever known.” I love you, Sally, I love you.” As soon as Geoffrey utters these words and the couple embraces, the sky begins to well up with uneasy clouds. Accompanied by old man McGregor, who has the typified Scottish accent warning them of the rough weather brewing.

As the foreboding torrential rainstorm quickly breaks the opening serenity, this symbol of strife and disturbance oppresses the joy and becomes a metaphor as the film ends with a similar rainstorm that besets Sally’s world.

This will inevitably turn into a nightmarish landscape for Sally. Still, the serene local diverts us from the darkness to come, as we soon discover that Carroll is a disturbed artist who constantly needs fresh female inspiration in order for his art and sexual gratification to thrive. His art depends on it, and he is willing to kill the women he once desired to sustain himself.

The couple seeks refuge from the rain in a nearby cave. As Geoffrey goes to get his fishing gear and picnic basket from McGregor, Sally remains behind, holding his jacket. As she calls after him, a letter falls out of her pocket. She picks up the small white envelope and is horrified to see it is addressed to Mrs. Carroll. The extraordinary range of emotions Stanwyck is capable of reflecting within a single frame is cogent and palpable as she shifts from content glances to an interior that aches. Her eyes glimmer with a crushed spirit. Franz Waxman’s dramatic score confronts the moment as the dark outline of the cave frames Sally.

Once Geoffrey returns to the cave, he finds Sally suddenly unyielding and in emotional distress.

“My wife.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?”

” I tried to from the first day, but I couldn’t. There’s a child, too.”

“Are you separated?”

“No, that letter was to ask for a divorce.”

“Have you been married long?”

“We’ve been together for ten years; my wife’s been an invalid ever since the child was born.”

“I know I love you.”

“I don’t want that kind of love.” Why didn’t you tell me before?”

“I didn’t want to lose you.”

“But it would have saved so much hurt, and now it’s no use.”

“I don’t believe that. “Before I found you, I was finished. There was nothing. I couldn’t work. I couldn’t think, I didn’t care. We mustn’t lose each other, Sally, ever. We couldn’t if we tried because our love is.”

Sally breaks down and flees the cover of the cave, crying, ‘No… no.’ Not wanting to hear Geoffrey’s excuses, she runs out into the pouring rain.

He gives a tortured look as symbolic bars of rain obfuscate his figure. As Waxman’s music acts like a buzzsaw in his twisted psyche, he looks down at the letter lying at his muddied feet and grips his head.

The scene switches to Blagdon (Barry Bernard), the cash chemist, sealing up a package with wax. He’s an unsavory character with a scar that gives him an added edge of sleaziness. Bladgon hands Geoffrey the register, “You’ll have to sign for this, sir.” Blogdan answers the phone; he’s lost a bet on the horses.

“I should say I do. It’s frightening, of course, and makes me shiver sometimes, but so definitely Mother. Do you think she’ll live until we finish the picture?”

Geoffrey Carroll returns home to his London flat where he greets his daughter Beatrice. He takes the little white package from the chemist and puts it in his pocket. Geoffrey asks how her mother is doing, and she tells him about the same.

He says, “What are you talking about, well of course she’ll live. What do you mean?”

“Don’t get excited, Father. We both want her to live because we love her so much. That doesn’t mean she will live, does it?”

A bell rings; it is time for Mrs. Carroll’s milk. Beatrice goes into the kitchen to prepare the hot white liquid for her mother. Geoffrey enters the room and takes the saucepan and glass from his daughter, pouring the milk himself. Standing outside the bedroom door, holding the glass of warm milk, a queer look sploshes over his face like waves of disequilibrium. He suddenly tells Bea that she’ll be going away to school starting tomorrow.

Penny-“Yes, but it’s a bit creepy, don’t you think?”

“That’s only at first. You get accustomed to it. Then you think it’s wonderful. She was my mother. Died a little less than two years ago.” “I’m sorry.”

“You needn’t be. We all die sooner or later.” Bea’s comment is calm and canny. Penny says, “I’ve heard a rumor to that effect.”

“It isn’t exactly as Mother was because it isn’t a portrait. Yet it is like her, too. Father says it’s representational.”

“Your father took the very word right out of my mouth.”

Two years later, Sally now the second Mrs.Carroll and Geoffrey are living in Ashton in Sally’s Gothic manor house inherited from her father.

Charles Pennington (Patrick O’Moore), or Penny, is greeted at the door by Christine (Anita Bolster), the housemaid. As he waits for Sally, he studies the painting of the first Mrs. Carroll, not noticing Beatrice sitting in the armchair. She tells him the painting is tremendous.

Ann Carter, as Carroll’s precocious daughter Bea, figures prominently in the film as the lens through which the conscience of the story reveals its moral code. Ann Carter exudes a mature seriousness reminiscent of Curse of the Cat People 1944 with her otherworldly air. She possesses a no-nonsense touch to the mixed-up morality she’s surrounded by that contributes to the pervasive despair and instability.

Barbara Stanwyck looks stunning as she enters the room. Sally tells Bea she needn’t leave, that Penny is a dear old friend. Bea tells her they’ve already met, and he’s ‘nice, quite nice.’ Penny asks how old she is, “45 or 50?’ “She does give that impression, but she’s sweet.”

Penny is kind and obviously still very much in love with Sally. In a very evolved and civil manner, he hasn’t forgiven her for running out on him. She feels terrible about it and says she should have given him some words. But when she met Geoffrey, when he came back, it was as if nothing else mattered. He tells her that all a disappointed suitor needs to do is look at her. He asks if she’s as happy as she looks. Sally tells him, “He’s good to me.” “He better be. Purely out of morbid curiosity, I should like to meet him.”

She tells him that Geoffrey is working upstairs in his studio and that she’ll call on him. Penny tells her that he’s not the only visitor. Mrs. Latham and her daughter Cecily are expected any minute. They’re his friends and clients.

Sally runs up the staircase, excited about her guests; she addresses the vinegary Christine.

“Tea for five! Bread and butter?”

“Yes, and some cucumber sandwiches.”

“Some cakes, too?”

“Well, if there are any.”

“We haven’t got any cakes.”

“Well then, don’t serve them.”

“I will.”

Waxman’s dynamically turbulent score breaks the witty moment as Geoffrey paces his studio. Throwing down his paintbrush and grabbing the canvas, he begins to rub the oil with turpentine, wiping away what he has painted with hostility.

“Something I should have done weeks ago; I’m sick of looking at it. A phony.”

“You can’t always paint masterpieces.”

“Well, I can always try.” “I don’t understand it, Sally, this fine old house, the most beautiful surroundings I’ve ever known, and you. I have everything here. Then why isn’t my work better? What’s wrong?”

Geoffrey begins to re-experience creative block with his painting, and his frustrations start to brew. He becomes combative with Sally, who has invited her ex-fiance, Penny, and two of his socialite clients, Cecily Latham and her haughty mother (Isobel Elsom-My Fair Lady, Ladies in Retirement, Love is a Many-Splendored Thing), for tea.

She tells him about their guests. “Your ex! What’s he doing around here? I think I’ll break his neck.”

“Don’t be silly; you’re not jealous of Penny.”

“Oh, you got some wrong information. I’m jealous of anything or anybody that takes your mind off of me for a single second.” He tells her to get along without him; he’s not going downstairs. But she insists that he should be social and meet her friend Penny and the other guests.

Geoffrey gives us a glimpse into his irrational jealousy. It’s also a fun homage to the last line he utters to Claude Rains in Casablanca five years earlier.

Christine brings a tray outside in the garden where Sally’s guests are lingering. Ordering Sally around, the maid tells her to cover the table with the cloth, “Those cakes you wanted, if I had any.” “There are none left.” Penny says he’s thrilled to have tea outside, but the acerbic Christine comes back at him, “Personally, I never cared for it since I was stung by a wasp.”

“Yes, but nothing I care to paint.”

As everyone sits around the table having tea, the tension between Geoffrey and Cecily emerges. Mrs. Latham (Isobel Elsom) is quite aware of her daughter’s sexually indiscriminate nature. “It’s awful how these modern young women will torture themselves for a little beauty.”

Geoffrey pacing while smoking a cigarette sits down and answers her “Oh I don’t know, it’s my opinion that beauty is worth any sacrifice.”

Cecily mentions that she saw his exhibition in London and refers to it as ‘stimulating.’ It was then that she decided she wanted him to paint her portrait.

Geoffrey and Cecily leave the table and go into the study. While they’re alone, she tells him about the three times she tried to flirt with him in the village and how he ignored her.

“Yes, I know. It’s fine. Brilliant really. Who was the model?”

“My first wife shortly before she died.”

“Hhm, strange, it should be displayed so prominently here. Doesn’t your present wife ever object to the fact?… Tell me, Geoffrey, do you always marry the women you paint?”

The only remnant of Carroll’s first wife is her monstrous portrait. She is never shown in flashbacks, merely suggested by Beatrice or Carroll’s point of view, yet we get a sense of her through the painting called The Angel of Death. This is her transfiguration as he made her sick to death.

Often, the first wife is never visually represented in these kinds of films. As in The Uninvited, Rebecca, Jane Eyre, and The Two Mrs Carrolls, the process of repetition is evident. The visual absence of the original woman is filled in with suggestions, traces of her existence, verbal references, or prominent paintings.

Once Penny and the Lathams leave, Geoffrey notices the chemist Blagdon outside in the front yard. He has figured out that Carroll signs his prescriptions as Fleming as a cover to murder his wife. He begins blackmailing him.

At first, Geoffrey and Cecily clash horribly, as their chemistry starts to take shape. When Carroll says, “Beauty is worth any sacrifice,” he desperately shows his fear of losing his artistic inspiration. At first, he doesn’t seem interested in Cecily, telling her she doesn’t represent what he wants to paint. But she soon becomes his new ‘subject,’ and he agrees to paint her. Then we see the gang at the races, where Geoffrey makes his first blackmail payoff to Blagdon. Geoffrey and Cecily exchange glances as the camera shows them holding hands. We now know the affair has begun.

At one point, Bea is reading a book on Van Gogh, and in one of the child’s insightful moments, she tells her father that it’s a shame such a brilliant artist went mad. Geoffrey grabs the book away from her and becomes irate, telling her that it’s ‘startling’ what she says. Sally has a profound grasp of her father’s true nature, even if no one else realizes it yet.

As Sally had challenged Carroll at the end of their sojourn in Scotland, Cecily threatens Carroll telling him she will leave him unless he takes some action and finally ends his marriage. She declares that she’s going to Brazil. He becomes increasingly agitated and intense and decides to leave with Cecily.

Soon after the affair begins, Sally has taken to her bed, weak and listless, not unlike the first Mrs.Carroll. She is told it’s a ‘nervous condition’ attended to by the jovial drunken country bumpkin Dr. Tully (Nigel Bruce), who drinks like a sot and is obsessed with the Ashton burglar and Yorkshire strangler. Sally wants to see a nerve specialist, but Carroll insists that she merely needs to have a steady diet of wholesome milk.

Sally has been ill for three weeks now, as Dr. Tuttle stands over her lying in bed, “Too much excitement is bad for you, you know.”She tells him, “If you allow me to get up, I promise to remain cool and calm and soothing and charming.”

She asks him what is wrong with her. “Actually, nothing very serious.”

“Why do I sometimes feel so weak?… Why do I have these splitting headaches I never had before?” He says, “It’s just a case of nerves, Mrs. Carroll. Nerves pure and simple.”

“I know, Doctor; heard all about it.” “Where’s your master?”

“Up in heaven.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“If you’re talking about my master, he’s up in heaven, but if you’re talking about my employer, Mr. Carroll, he’s out in the garden.”

“Garden, what’s he doing out in the garden on a day like this?”

“Minding his own business I should think”( to herself ‘Nosey old fuss.’)

The story originally was meant to be a darkly comic thriller. Christine and Dr. Tuttle add a streak of humor to the otherwise dark tale. Bogie is creepy, chilling, and menacing in his role as the deranged vampiric painter.

Tuttle helps himself to Carroll’s spirits. When Geoffrey catches him taking a drink, he tells him it’s for medicinal purposes, staving off a cold. Geoffrey tells him to have another; it might get chillier.

“I say, have you heard that the burglars’ on the prowl again? Last night.”

“Yes, I heard about it.” “Who told you?” “Christine.”

“Probably told you all wrong. Women never get their facts straight.” He tries to continue his fascination with the recent rash of crimes, driving his obsession with the burglar/strangler, but Geoffrey tells him there are more important things to discuss.

Geoffrey tells him that he’s been looking into a nerve specialist and would he have any objections to getting a second opinion. Tuttle tells him if it put his mind at ease he’d welcome another doctor’s opinion. In that case, never mind. Geoffrey tells him that he was just testing him and that Sally hates being ill. “Funny thing most women love it” Tuttle replies. Dr.Tuttle acts as the dismissive force in this woman’s paranoia themed film.

Sally tells Geoffrey about Dr. Tuttle, ” If they ever took the word nerves away from him, he’d be out of business.”

Geoffrey has now started working on a new painting, which no one will see until he is finished.

She asks him, “Do want to make me very happy? Let me see the new picture you’re doing.” He answers no. “But why I’ve always seen all your other work?”

“No one’s seen this work, and nobody’s going to until it’s finished.”

“When will that be?”

“Soon, very soon now. Who knows, it may be one of those masterpieces we were talking about.”

He tells her he’s leaving for London with the prospect of a new commission. She’s happy for him. He’s also told his daughter that she’s been accepted to a private school and will be leaving shortly.

After he leaves, Sally finds one of Latham’s Victor Hugo roses in the study. A light flashes for Sally. Earlier, she told him that she thought she had heard a woman’s voice that morning, but he told her it was Bea. Sally asks Christine, “Was Miss Latham here this morning?” “No, not that I saw.”

Christine is setting the dinner table for the guests. She tells Sally that Bea is upstairs packing because she’s going off to school. There was a call from London. Sally asks if she knows who it was. “Oh yes, he’s called several times before; his name’s Blagdon.”

Sally assumes that Blagdon is the headmaster of the school Bea will be attending. She goes up to Bea’s room where the little girl is meticulously packing. This signals that she is about to die.

“Why not?”

“Father says I wasn’t to bother you about it until we were sure.”

“Judging from all this, you seem to be quite sure.”

“It’s the Weatherly School, Sally, one of the very best. Aren’t you happy for me?” “Of course, I am, darling. I’m delighted. Only I can’t understand why your father”(she pauses). Let me help you with some of these things.”

It is here that her father’s deception and dangerous lies come rolling out of the mouths of babes, as Bea so matter-of-factly informs Sally about the way things really are.

“I bet I am. I know Father, when it comes to these matters. Last time I went to school he decided on a Wednesday and on Thursday there I was in school.”

“That was sudden, wasn’t it?”

“One of the teachers helped me with my clothes at that time. Mother was too ill to help me very much. Mother had such wonderful taste. Usually, we did all our shopping together.”

“That must have been fun for you.” But going to all those shops, didn’t that make her very tired?”

“Tired? Mother? Nothing ever tired her. She was wonderful at sports. She used to beat Father at tennis all the time. Father didn’t like that very much.”

The sudden awareness that washes over Sally is heartbreaking as she begins to realize that her life with Geoffrey has been an agonizing lie, one that soon becomes a threatening truth.

“I don’t understand if she was an invalid…”

“An invalid”¦ where did you ever hear such a thing?”

“I don’t know ( Stanwyck conveys a faintly present woman in peril as the chilling awareness of the truth seeps in; she can barely speak). Someone told me once.” “Oh no, you’re very wrong, she was in perfect health until… Sally, you haven’t seen Father’s new portrait of you, have you?” Sally tells her, “No.”

“Darling, does it hurt you to talk about your mother?”

“No, not anymore.”

“Then tell me, you were saying she was in perfect health. When did she become ill?”

“I can remember that only too clearly. It was shortly after Father returned from one of his trips.”

“The trip to Paris or America?”

“No, it was a short vacation for him, really. He’d gone fishing in Scotland. When he came back, he began to paint Mother as the Angel of Death. The finest thing he’s done, too. And it was far from easy. Mother would have those splitting headaches and feel so terribly weak. Then she’d be a bit better. Not for long, she.”

Stanwyck sits quietly, expressing an internal torment, eyes flickering with tears as she listens to the revelation of her husband’s hideous nature unfold. The first Mrs. Carroll had been sick with the same symptoms and had only been ill a few weeks before she died, not an invalid since the birth of Bea.

“I wouldn’t have mentioned it if I hadn’t been ill myself.”

“Oh, but yours is only a nerve condition, Sally. Everyone knows that.”

“Yes, and your father’s been so considerate.”

“He’s always the same. When Mother was ill, he insisted on taking care of her. Bringing her the milk himself. “

Marlisa Santos refers to this in The Dark Mirror: Psychiatry and Film Noir as ‘Carroll’s cycle of creative vampirism.’ He seeks to draw inspiration from his female subjects through his painting and sexual relationships. Santos also makes an interesting point about the use of milk as a way of inflicting death or drawing away life, and suggests that in the final stage of his psychosis, using milk is a reversal of the symbolic metaphor of vampirism. Instead of drinking the victim’s blood as a source of life and vitality, the whiteness of the milk represents not only an emptiness or emptying out of the person’s substance, but also signifies what they’ve become to him -nothing.

I think milk also represents a way to regress the female subject back into a child. The victim ‘subject’ has lost her sexual vitality to Carroll, whose male gaze has now deemed her neurotic. The fact that the illness manifests itself by proposing that they are suffering from ‘nerves’ reduces them from the sexual subject incapable of inspiring him. Carroll’s psychosis parallels vampirism as well, bringing another element of the horror story to the narrative.

Sally approaches Christine again and asks about the man on the phone, “I spoke to him once; he’s most unpleasant.” “What does this, Mr Blagdon, do?” “He’s a chemist.”

And so begins the Suspense/Noir use of Voice-Over in Stanwyck’s own voice as she talks to herself in the second person. “It’s all very clear now; he’s poisoning you.” Sally becomes the archetypal hysterical woman as she cries in desperation, “No, no!”

Sally goes with Bea up the dark and winding iconographic stairs to look at the mysterious portrait in the secret room, although she already has a sense of what she’ll find. It will be the final unveiling of her husband’s mental illness. Bea is the only one who has a key to her father’s studio and is the only person who truly understands her father’s deranged psyche.

Mary Ann Doane in her book, The Desire To Desire gives insight, “The staircase in the paranoid woman’s film simultaneously becomes the passageway to the ‘image of the world’ or ‘screen of the worst. ‘ In Dragonwyck noir lighting intensifies the sense of foreboding attached to Gene Tierney’s slow climb up the stairs in the attempt to learn what her suspicious husband does in the tower room off limits to her. Both title and mise en scene of The Spiral Staircase depend on the central icon of the genre. In Sleep My Love the space of the house is dominated by three tiers of stairs on or rear which the female protagonist is attacked by distorted voices.”

What Stanwyck’s Sally finally discovers in the room at the top of the stairs is her own distorted and grotesque image in a portrait, evidence that he plans on killing her.

Bea and Sally enter the dark room of Geoffrey’s madness. As Kristeva states, ‘the place where meaning collapses.’ The night is windy and threaded with downpours. The weather has come full circle from that first day in Scotland inside the cave when she finds the letter and realizes that Carroll isn’t what he pretends to be. They open the door, and Bea walks over to the easel first. She gasps once she sees the painting of Sally as the Angel of Death, with dark sunken eyes and a body that looks almost skeletal. The current of raindrops flows across the canvas, drowning the grotesque image. Sally slowly verges on the sinister portrait, taking slow steps in chiaroscuro and then fainting at the sight of her impending fate.

When Stanwyck’s Sally sees the grotesque image of herself in her husband’s painting, it echoes the abstract portrait of his first wife, The Angel of Death. It’s an instance of self-confrontation, a narcissistic framework or awareness that produces the collapse of the ‘subject/object.’

The woman in this kind of filmic narrative confronts the non-object of her own fear; she is literally confronting herself. As Linda Williams lucidly demonstrates in her writing about horror films, the monster acts as a kind of mirror, reflecting back to the woman an image of her own lack, a form of female ‘castration.’ The monster, or here the image of Sally as a grotesquely distorted painting, acts as a horrifying exhibitionism equivalent to that of the woman.

The ‘female paranoia’ Gothic film definitely seems a kindred spirit to the horror film, positing the woman in peril as the one who looks and ultimately reveals the existing terror, invoking the ‘monster.’Â Here the subject of monstrous femininity is personified in works of art depicted by deathly women.

As Julia Kristeva describes in Powers of Horror; “The place where meaning collapses,’ is in our culture the place allotted to a femininity which is excluded from language and the symbolic order.” Later, Kristeva refers to her concept of the abject as “The horrible and fascinating abomination which is connoted in all cultures by the feminine.”

In Jane Eyre, the place where meaning collapses is the space given to the madwoman from the point of view of a room filled with blackness. In The Two Mrs. Carrolls, the place where meaning collapses is Geoffrey’s studio, which harbors the iconic painting that signals Sally’s fate.

Waxman’s climactic music underscores the enigmatic moment as Bea cries and caresses Sally, now unconscious on the floor. “Sally dear, Sally!” Bea weeps; this is the most emotional moment she’s had in the film.

Sally is thrown into a nightmare of love that turns to death, as she becomes the symbol of the ruination of Carroll’s artistic inspiration. His mental illness takes the form of Vampiristic hunger that feeds on the life force of his love objects as nourishment for his creative process, discarding his ‘subjects’ once he has drained them of their sexual vitality.

Both Freud and Hollywood love to tie female paranoia to the mistreatment of visual representation, which can be served by either the abstract or symbolic patterns of representation of the real thing in art. Bogart’s character of Geoffrey Carroll signifies his mental illness as an abstraction that is not clearly delineated within a classical Hollywood narrative. When Carroll’s paintings maintain their value in terms of their exposition of the ‘subject,’ which fulfills his desire, then his women and the marriage exist in a safe environment. It is only when he begins to feel dissatisfaction with his work, which is only an abstraction of his sexual insufficiency, that it triggers a murderous desire, signally a transformation into violence and his need to kill his ‘subject/object.’

The use of a painting to represent victimized women can be allied with Freud’s case of female paranoia, where he treated a woman’s delusions surrounding having her photograph taken by two men who intend to use the compromising photo to harm her.

Paranoia and the reflective image of a woman in peril through the use of a portrait were consistently used in the suspense film of the 40s, using a psychoanalytic portrayal of female phobia. The Two Mrs. Carrolls falls very nicely into the cycle of films set off by Hitchcock’s adaptation of Daphne Du Maurier’s novel ‘Rebecca.’ This cycle of films could be considered ‘paranoid women’ pictures, where the wife fears her husband is plotting to kill her, and the conventional ceremony of marriage is bound up in a nightmare and plagued with threats of violence. Often, the scenario, as with this film, shows a hasty marriage to a man who is virtually unknown to the woman. Sally gets a glimpse of Geoffrey’s duplicity on that rainy day in Scotland, yet she ultimately marries him after his first wife dies. Lang’s Secret Beyond the Door’s use of flashback shows Joan Bennett on her wedding day and the image of Michael Redgrave coming out of the shadows at the church as the revelation in Voice-Over: “I’m marrying a stranger.”

As Thomas Elsaesser says in regard to the film Rebecca:

“Hitchcock infused his film and several others with an oblique intimation of female frigidity producing strange fantasies of persecution, rape and death. -masochocistic reveries and nightmares, which cast the husband in the role of the sadistic murderer. This projection of sexual anxiety and it’s mechanisms of displacement and transfer is translated into a whole string of movies often involving hypnosis and playing on the ambiguity and suspense of whether the wife is merely imagining it or whether her husband really does have murderous designs on her.”The Woman’s active investigating gaze is simultaneous with her own victimization. The place of her specularization (the stairway) is transformed into the locus of a process of seeing deigned to unveil and aggression against itself.

Also in these films the house becomes the analogue of the human body, it’s parts fetishized by textual operations , its erotogenic zones metamorphosed by a morbid anxiety attached to sexuality.”

At this point, I’ll leave the story here and let you find out what happens as this suspense-thriller unfolds.

The Two Mrs.Carrolls allows Barbara Stanwyck and Humphrey Bogart to be reflexive and compelling as both villain and victim. Stanny is radiant even as she slowly comes to terms with the true nature of her marriage to a psychopath. Moving about the Gothic structure of the house in an Edith Head creation makes her appear as a classy damsel in distress. Although afflicted with the archetypal hysteria that these kinds of films foist upon their female leads, Stanny wears her trepidation with an iconic elegance and tenacious internal force of nature.

Make sure to always drink your milk! – Your ever-lovin’ Joey!

Great screen caps — I feel like I’ve been able to see this terrific movie again.

I always thought the casting in this movie was clever, with Stanwyck as the “good” wife and Alexis Smith as the other woman. Bogart is great, too, because you never really know what he might do next, and you’re always wary of what he’s capable of.

Wonderful post! :)

Hi Ruth! I enjoyed your Stanny post on The Strange Love of Martha Ivers too! Stanwyck was great whether she was playing the good wife or the immortal bad girl. She had great dimension- and I mean that in every way-I adore Bogie, and he really did create a creepily sinister husband. Kind of squirrelly but scary still. Thanks for the kind words my friend! See ya soon for your much anticipated The Old Dark House for The William Castle Blogathon!!!

Very interesting information about the psychological background and the whole series of paranoid films with sinister husbands stemming from ‘Rebecca’. I’ve read that the release of this was delayed because of similarities with ‘Gaslight’, but the milk is definitely reminiscent of ‘Suspicion’, as you say. The paintings of Barbara Stanwyck and the other wife in this were by Hollywood artist John Decker, who also did the paintings in ‘Scarlet Street’.

Hi Judy-I really enjoyed covering Mrs Carrolls from the psychological perspective because the film was rife with the sort of stuff films of this type were starting to dip their toes into. The whole woman-in-peril picture fascinates me, especially the sinister husband angle. In particular Lang’s Secret Beyond the Door with Joan Bennett being one of the best I think. I can see why they wouldn’t want to compete with ‘Gaslight’- Thanks so much for the added info about the paintings. Just a wonderful little tid bit of interest to add to the allure of the film. I appreciate you stopping by- Cheers Joey

Thanks, Joey, I’m interested in the woman-in-peril films too, so will look out for ‘Secret Beyond the Door’.

Great write up of a film that I’ve always been ambivalent about. I’m a fan of Bogart in almost all of his films but think he’s as wrong here as he was as the Irish stable hand in Dark Victory. His on screen psychosis in many of his early films was of the mad dog variety and he was electrifying but that’s not the creeping madness required here and to me he seems ill at ease. I could see Paul Henreid, Fredric March or even Rex Harrison all being more at home in the role.

Missy is great of course although the somewhat weak sister she plays didn’t utilize the full breath of her talents. Ann Carter was an interesting little actress, never understood why she didn’t have more of a career. I know she was stricken by polio but her career hadn’t really moved forward like it should have before that. Then of course there is the wonderful Isobel Elsom, always a joy with her brittle sophistication and high class hauteur, one of those marvelous character actresses that provided a world of backstory just by their presence.

Someone who is perfectly cast is Alexis Smith. Her silky villainy is a joy assisted by her eye popping wardrobe. She’s a perfect example of a studio not taking proper advantage of one of their contract players. She proved herself adept at every genre they put her in, perhaps that was the problem she was too beautiful and too at ease in standard parts. She didn’t have a rebellious reputation, maybe at the time she was content with what she was assigned but once free of the studio shackle she certainly proved there was more to her than had previously been utilized.

Not a major film for any of the stars but still full of the Warner’s high quality production values and sheen. A good rainy day film.

I love how much depth and detail you bring to this review. To be honest, I’d kind of slotted The Two Mrs. Carrolls away as a bit of a disappointment. Even though I’m a sucker for Gothic thrillers, I wasn’t won over by Bogart’s performance or by the lack of development in his and Stanwyck’s romance. Unlike Rebecca and Dragonwyck, we don’t get to watch the couple fall in love and I think that makes a big difference. However, you’ve made an excellent case for the movie’s strengths, which includes the atmosphere, the visuals, Stanwyck’s wonderful wardrobe (I think she looks fantastic here), and Ann Carter. I think Alexis Smith gets my vote for MVP of the Movie since she’s so sinuous and sexy here and steals every scene.

The connections you draw in this review are all fascinating. I especially like your comparisons to Secret Beyond the Door which is a perfect complementary example of the whole Bluebeard theme. I’m also completely enthralled by your beautiful screencaps. They make me want to watch the film all over again and just soak in the Gothic atmosphere.

Thanks for this great review and for participating in the Barbara Stanwyck Blogathon.