“Lunatics are similar to designated hitters. Often an entire family is crazy, but since an entire family can’t go into the hospital, one person is designated as crazy and goes inside” -Suzanna Kaysen from Girl Interrupted (1993)

What Ever Happened To Baby Jane (1962) Directed by Robert Aldrich. The film stars Bette Davis, Joan Crawford Victor Buono, Marjorie Bennett, and Maidie Norman as Elvira

“But you “are” Blanche, you “are” in that chair!”~ these are the words I often utter to myself or amongst friends, merely cause it tickles me.

I could question whether or not Aldrich made these films as a vehicle in which to translate the lives of the psychologically intricate, often tragic women which he viewed through a sympathetic lens, or perhaps some of his female-driven films are an exercise in misogyny.

So was he a misogynist? Perhaps some might find the portrayal of his female characters unattractive, or maybe he didn’t differentiate between his male and female roles. He was definitely more focused on both genders’ struggles. These outliers of society couldn’t simply fit in, so if the film’s driving character happened to be a woman then it would stand to reason she would also be an outcast or damaged in some way. If he did make a distinction as to gender, he was mostly preoccupied with the character’s system of dealing with the obstacles they faced in their lives. It does appear that his “women” usually are the solitary focus, while his “men” are framed as groups of men trapped by precarious situations.

Robert Aldrich is still one of my all-time favorite directors.

Aldrich always brings us a story that is cynical and gritty with very flawed characters who are at the core ambiguous as either the protagonist or the antagonist. Aldrich studied economics in college, then dropped out and landed a very low-paying job at first as a clerk with RKO Radio Pictures Studio in 1941.

He studied with such great directors as Jean Renoir and it was his training in the trenches that made him the auteur he is, delving inside the human psyche and questioning what is morality. Aldrich went on to become the assistant director, scriptwriter, and associate producer, to various filmmakers who were later on targeted by the blacklist.

Aldrich has a flare for the dramatic, he likes to break molds and cross over boundaries. He also has a streak of anti-authoritarianism running through the veins of his films. There aren’t just traces of his ambivalence toward the Hollywood machine in his film philosophy, he also conflates the ugly truths beneath the so-called American Dream and the “real” people who inhabit that world.

He died in 1983, And while he remained inside the Hollywood circle, he maintained an outsider persona. He memorialized the misfits and outcasts by making them the anti-heroes in his work, all of which ultimately were destined to fall because they refused to play the conformity game.

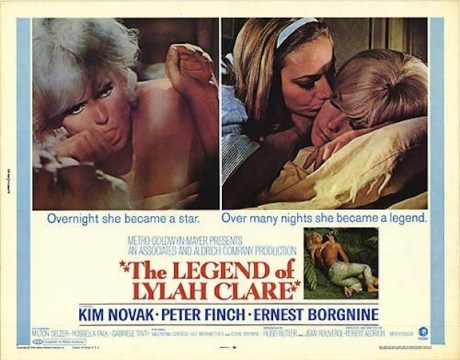

I chose to focus on Baby Jane and Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte, as they are not only my favorites of his, but also they are 2 incredible pieces of film art, and while Aldrich has a huge filmography to his credit like his Cold War scare Noir masterpiece Kiss Me Deadly, his memorable film that exposes the flawed Total Institution of the penal system, The Longest Yard with Burt Reynolds, and his iconic war film The Dirty Dozen. His other psychological thriller with Joan Crawford playing wife to the psychotic Cliff Robertson in Autumn Leaves and the 2 Hollywood ventures exposing the dark side, The Big Knife with Jack Palance and Kim Novak in The Legend of Lylah Clare.

I am focusing on Women in Peril as an ongoing series that I’m featuring and these 2 films fit nicely into this theme.

In retrospect, Aldrich definitely does not paint his female characters in a very good light, literally and figuratively. Still, I think Baby Jane and Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte which will be continued in Part III & IV of this commentary, are incredible pieces of work, memorable on so many levels, and just a downright fun indulgence to watch.

Interestingly enough, I did find myself growing increasingly more sympathetic with Jane after viewing Baby Jane several times recently, as I started to humanize her more as a tragic victim and not an insanely vicious nutcase.

And I can’t imagine that I’ll have ruined the film for people, as it’s highly unlikely that there’s anyone who doesn’t know the story.

Especially if you’re like me and know several wonderful female impersonators, mine live in NYC. So you’ll have to forgive my presumptive post and allow me the luxury of seeing the film through to the very delicious finale in Part I of my post.

I’ll even name a cat Blanche one of these days if it suits her. Perhaps a Siamese like my Daisy, who was a rescue of course. I already have a cat named Tallulah.

First of all, I LOVE Bette Davis with a passion, the actress and the woman herself. Have you ever seen the fabulous Dick Cavett interview? if not you should track down a copy and watch it. Bette is one of a kind, she has a distinct style, a unique “hitch to her git along”, as Andy Griffith would say, a true Hollywood icon, and thoroughly delightful and dynamic!

And I admire Joan Crawford as well, she was unbelievably beautiful when she first started out in motion pictures before the crazed galvanized eyebrows took over her face. It makes me sad to think that these women despised each other, it’s a shame really. And I don’t want to get into the whole Mommy Dearest aspect of Crawford’s life. I am commenting on her work in Aldrich’s film, not her personal life. Eyebrows notwithstanding.

Another reason I want to talk about Aldrich’s’ 2 seminal films, in particular, is that these 2 works set the tone for other films to follow. Aldrich’s 2 Melodramatic Noirs or what I like to call Melo-noir films being the most memorable for me at least started a cinematic trend.

The grotesque melancholy, the wasteland of forgotten womanhood, and abject psychosis drenched with the repressed woman-child born of rage and delusion.

Again if I were to sit with a feminist scholar or watch these films with a sociology of gender Ph.D., I might find several reasons to be angry with Aldrich’s lens. But to quote either Freud or was it Groucho Marx? “Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar!” Meaning, that as a contribution to the Gothic Horror and Melo-Noir genres, What Ever Happened To Baby Jane and Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte are masterworks, at creating the monstrous feminine atmosphere. Cringe-worthy, yet oddly sympathetic, and absolutely unforgettable.

Delayed opening credits and prologues are signatures for Aldrich. In the opening credits of Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly (1955) written by Mickey Spillane there is a sound of a woman either crying, gasping for air, or breathing heavily from sexual pleasure. I do know that it’s Lily a double-crossing femme fatale who eventually opens up Pandora’s Box and creates Hell on Earth for Southern California.

Baby Jane has 2 prologues which equal 12 minutes in length before the titles even roll. This time, it’s a child who is sobbing against the black screen for several seconds.

One thing that struck me first was the song Jane performs “I’ve Written A Letter To Daddy” which really appears to sexualize Jane as a child. The tune is about Jane’s devotion to her father. There are undertones of an incestuous relationship between father and daughter, at the very least it’s an inappropriate boundary that has been crossed between them. Jane’s father teaming up with her as a performing partner at the piano then finally joining her to dance, makes them appear as if they are a romantic couple. The blurring of the roles in the family must have added to the twisted sense of self that later formed Jane’s regressive behavior.

In both What Ever Happened To Baby Jane and Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte Aldrich employs a monstrous hybridism of grotesque femininity and latent childhood development culminating into deranged behavior and antagonistic aggression. And I don’t call myself a feminist however that term is supposed to be defined these days, and I only live with a Sociology scholar, I don’t play one on tv. I’m just a songwriter who’s also a rabid Cinephile when I’m not playing piano or wrangling my cats.

This lurid tale, this pulp melodrama of abject madness is superb, particularly because of the uninhibited performances by Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. Aldrich directed this film with crude veracity leaving us to dwell on some feelings of ambivalence toward these particular characters. As I said earlier, I was with Jane even at her cruelest, although I pretend that the bird died of natural causes and the rat was found that way… I never warmed up to Blanche, I remembered that “she’d remember” and even though she was an invalid, I got the sense from her that she was not what she appears to be.

We are given 2 parallel points of view. That of Jane’s obsessive instability and narcissism and Blanche’s stoicism and experience in captivity. Any passage of time loses its meaning. Time is actually suspended or swallowed up by the aggressive or belligerent framing of the narrative. It is the tense and suspenseful tonality that serves to ramp up the film’s gutsy devolving. The counterbalance of Jane’s succession of jaunts out of the house into the real world with just a minimal amount of human contact contradicted by Blanche’s captivity, making several attempts to escape yet always failing, is in fact modulated by their contrary realities.

Blanche’s trajectory in the film is about deprivation. First, she is already bound to her wheelchair from the car crash that smashed her spine. Then, Jane takes her mail and hides any notes from the neighbor. She rips all the phone wires out of the wall within reach of Blanche, or she takes the phone off the hook. She then ties Blanche up and tapes her mouth shut, so her mobility and speech are restricted even more until it ceases altogether. Both hands are bound by chains rigged to the ceiling. And not for good sex either!

Then there is Jane’s method of starvation. Blanche is not only nutrient deprived, but she is also psychologically tortured into fearing her food.

Blanche is dying by attrition. I have to say that I don’t believe it was Jane’s intention to starve Blanche to the point of death, I maintain that she found Blanche’s interfering and the idea of selling what she perceived as “her” house, threatening and so retaliated in order to control the situation. As irrational and regressive as she is, it would make sense that she would torment her sister, virtually like a childish bully.

Jane didn’t really have to murder her sister in mind. She just wanted to thwart and frustrate her into submission. She even states later on, when she’s reminded about the accident by Blanche and Jane recoils from the suggestion “I couldn’t do that to you” and it wasn’t her fault about Elvira, she was provoking Jane, she tells Blanche. “I don’t know why Elvira would make me do that”

Since Blanche is not permitted access to the phone, she cannot reach out for help in any way. Her loss of freedom as it progresses in the film and ultimately potentially her life? makes this truly a horrific experience. What gives the film its cult status and makes it stand out from so many others of its type are the performances by these two actresses and the way Aldrich sets up the film’s narrative.

The past “flashback” which is the opening prologue continues to insert itself into the present. Blanche starts to get fan mail, the television station runs a tribute to Blanche’s old movies. The neighbors bring flowers and gush over Blanche and the macabre and grotesque reenactments of Jane’s childhood vaudeville routines. The rehearsal room equip with footlights, is littered with newspaper clippings, sheet music of songs only a little girl would sing, and of course that omnipresent giant Jane doll that might even be scarier than Chucky. You decide.

The doll almost acts as alter ego, and also seems to be Jane’s one and only trusted companion. This only goes to prove that she is clinging to herself and the last fringes of her identity for dear life.

The narrative itself has essentially become yet another form of entrapment.

It’s the way the narrative is organized that creates a claustrophobic world, a closed system with no escape route. Especially since the expectations of escape for Blanche diminish with each scene. In fact, we don’t ever really have any resolution, because it’s never revealed whether Blanche dies out there on the sand, or if she manages to recover later on. We aren’t given that information. The epilogue is merely Jane swirling and prancing around fully regressed as Baby Jane Hudson on a sandy stage at the beach.

In Peter Shelley’s book Grande Dame Guignol Cinema- A History of Hag Cinema from Baby Jane to Mother, he compared the way Blanche looked at the end, with her pasty death mask and dark rings to the actress Irene Papas. Maybe it was the eyebrows.

The vast extremes come after all the physical and emotional restraints of the dark imposing house with heavy Gothic furnishings throughout its interior of Baby Jane when it shifts at the climax to the bright daylight of the beach. The contrary environment of an expansive, sunlit landscape we are left with in the end is startling. Like trying to adjust your eyes to the sun, after being in a really dark room for hours. From the long view, the camera shoots Blanche in drabbest gray on a black blanket, the police and on-lookers seem more like worker ants encircling their queen.

As in Film Noir Aldrich’s visual style purposely uses framed shots and ironic aspects of the narrative. The extreme use of angles and foreground clutter are mechanisms to represent the instability of the characters. All this serves to create the claustrophobic sense of walls closing in and reinforces the sensation of entrapment and desperation.

Even Blanche’s bed frame seems like a set of bars. The dark furnishings like the wrought iron and dark wooden curves of things create an impressionistic prison. More often than not, the characters are viewed or are gazing through some type of literal framework. Bars for those peering in, and bars for those gazing outward. Window bars, the steep staircase, much is seen through a lattice lens that traps our gaze. And on several occasions, there is an exterior shot of the house, with windows barred, either in the shadow of night or light of day. Essentially, even the scene of the car crash, virtually leaves us with a vision of a mangled iron gate, foreboding the inevitable.

I also noticed that a lot of the shots of Jane share her reflection in the mirrors. Mirrors are symbolic of self-reflection. We see the 2 Janes with Edwin. When she is rehearsing with him. Throughout the film, there are various moments where the screen shows us 2 Janes being reflected back at us.

When Jane goes into Blanche’s room after Edwin finds her held captive, she asks Blanche for help. Blanche is in total darkness, and the only light is shed on the portrait of Blanche above her bed, painted when she was a movie star. The light is illuminating the actress Blanche like an angel, but the real Blanche is in total darkness. The painting is an illusion of Blanche’s goodness. We see both images in the same frame which sets up the duality.

Again we see the dualities of the characters. The contrasting aspects of the characters from different times are juxtaposed and played out in one single frame. This is a way Aldrich subtly lets us know that there are 2 sides to each of these characters and their story.

Again, as mentioned in Peter Shelley’s book “the shots of overhead views of Blanche spinning helplessly around in her wheelchair have multiple expressive implications from that of a trapped bug in a jar”

Like a caught bug in a jar, Blanche is confined physically by her paralysis and literally by her restraints, while Jane is imprisoned by her deteriorating sense of reality and her shifting into madness.

I think on some level Jane knew the truth about the accident and that’s where the animosity came from. But she was so vulnerable from the drastic loss of attention as a child celebrity, the drinking problem, possible abuse by her father, the police brutality, and Blanche who set it up to look like Jane caused the car crash, accusing her of the accident and/or never trying to repair the perception of Jane’s guilt or innocence, thus implicating herself as a murderous.

All these triggers conspired to make Jane split off, not seek or receive the proper help, ceasing the development of a healthy life, or maintaining a good self-image. The real horror of the film is based on how much we as humans are capable of self-loathing.

It was this ambivalence that Jane couldn’t reconcile with which caused her to actually mentally fracture. The guilt of causing the accident, the resentment and anger at herself turned outward toward Blanche whose career was more successful. Jane cracked from the strain. She drank to forget, she drank to remember or block out the inner voices, the instincts that told her it was Blanche who tried to kill Jane and essentially ruin her life.

Baby Jane was not completely shot exclusively in shadow. We get the feeling of the proximity to exterior light which is there to give us a sense that Blanche’s freedom is so close yet so unattainable. There are scenes of Jane’s grotesque makeup that are lit very starkly or carnivalesque which adds a visual garishness to represent Jane’s madness.

Aldrich’s also used a depth of field with his camera as a way to accentuate how restrictive Blanche’s environment is. The telephone is seen in the foreground as Blanche drags herself down the steep stairs. This creates an ironic exercise in futility which is based on the liminal view of the action. The phone seems to always remain out of her reach even though she is exerting all her energy to move down the stairs. The telephone is yet another symbol of freedom for Blanche yet its constant distance from her represents the futility of any escape. So the potential of freedom is visible yet not accessible to Blanche. However, the buzzer that Blanche uses to summon Jane is a constant source of irritation to Jane, and yet Blanche lays on that button like it’s giving out golden eggs!

The exterior light is relevant to the stability and freedom outside the boundaries of the house. Jane is alternately the child star when she retreats into fantasy and wrenches back into the present as a begrudgingly adult caretaker and the one way she can dominate Blanche.

Through Jane’s complete regression, more light is let into the environment. She will be delivered from the dark environs of her madness, and her own enslavement of caretaking of Blanche, and now that everything is out in the open, perhaps she’ll get the help she needs.

On some subconscious level, Jane understands that to shake off the past and recognize her repressed violence and antagonism would mean certain annihilation of her current fantasized identity. We know that she has twinges of cognizance when she asks “What ever happened to Baby Jane Hudson?” or when she tells Blanche “They were too busy putting out your crap” to show one of Jane’s best pieces of acting in a picture the studio failed to release.

Reducing Davis’s performance to histrionic campiness would diminish the moments when she is starkly in control of the serious meter of Jane’s growing madness. The oscillation between Jane’s childish tantrums and musings and the all-out fury and retaliations is quite an artful feat delivered by Davis masterfully. She must have enjoyed the role immensely. It must have also been challenging.

I think this is why Aldrich gave Blanche the longer reaction shots because she is essentially the reactive character. When Jane puts the rat on Blanche’s dinner platter it’s Blanche we see crying, while we hear Jane’s sardonic cackling simultaneously. We often see long-held shots of Blanche’s expressions.

The vulgarity and brashness of the film can be considered a way to materialize a stylistic extreme or indulgence to reflect back at us the “spectator”, the character’s conflicts and emotional states of mind. Essentially we are at the mercy of Jane’s madness as is Blanche, which ultimately drives the entire film. It stands to reason that Jane would represent a truly Gothic character whose emotional turmoil is sent into a whirl because of the isolation of the narrative. And it perpetuates both Jane’s and Blanche’s psychological strain from what is normal. Yet I’ll state again, I felt more pathos for Jane. Especially by the 3rd viewing. With the exception of killing Elvira, I find Jane funny and actually charming when she wasn’t feeling that she was being looked down upon, judged, or ignored.

Jane’s dissipated drunken swagger, the way she literally slouches around the house, and her irritable disposition might be the culmination of not only 30 years of taking care of Blanche, but also a sign that she is inappropriately uninhibited by her years of the undigested bile of animosity, hostility and ultimately her malicious outbursts of paranoia, that lead to her aggression and violence.

Let me just talk about the pleasant (Eewww!) Edwin for a sec. There’s something obscene about the way Edwin focuses on the position of the doll’s leg being splayed outward and mentions that she can’t be comfortable like that.

Is it that he is mocking all females indicating by the script that he is a cipher, in fact, a latent homosexual, or is it just a misogynist gesture to manhandle it as an object of the female body? Or is every female figure his castrating mother?

When Edwin runs up the stairs and discovers Blanche bound and gagged, he’s so much bigger than Jane he could have easily subdued her and save Blanche but he was struck still, stunned and barely saying “She’s dying, dear god, she’s dying,” yet he does nothing to help. He tries to stop a car, by waving his hands, but we don’t know if that’s for him to get as far away from the horror he saw or to get a lift home. Was he too traumatized to react or was he trying to get other people to help him? We never find out.

Both Edwin and Jane share this childlike quality. Perhaps a little boy wouldn’t know what to do and would panic and run. They share this pathology as adults living as grown children barely functioning in the world if not for the adults in their lives like Blanche and his mother Dehlia to define it for them.

In the end, Jane’s macabre corpse white makeup, painted like a mask with heart-shaped beauty marks, Kewpie-doll lipstick and blond wig of massive banana curls give Jane an extra bizarre persona. While Jane is supposed a vain character ironically she is under the impression that she is fashionable, counterintuitive to her vanity, she is a vaudeville clown with caked-on face powder, and slouchy dresses that are adult versions of the Baby Jane stage outfits she wore as a child. When Jane goes out in public wearing the fur and wilted corsage and antique jewelry, it represents her attachment to the past, although it is not flattering to her at all, when in fact she is perceived as pitiful.

Apparently, it was Davis herself who created the chalky pale freakish make-up that Jane puts on when she starts to plan her comeback. It’s almost a decrepit version of the artist-painted face of Geisha culture.

In contrast, Blanche’s dark circles under the eyes and cadaverous pallor from malnutrition give her a deathly look compared to Jane’s exaggerated theatrical guise. This vulgarization of Jane portrays her as infantile and psychotic while Blanche is revealed to have been a vindictive assailant who might have succeeded in killing Jane.

It stands to reason that Jane would represent a truly Gothic character whose emotional turmoil is sent into a whirl because of the isolation of the narrative. and perpetuates both Jane’s and Blanche’s psychological strain from what is normal.

In terms of this picture being merely a melodrama, would be missing the margins because it incorporates an atmosphere of Gothic regression, not unlike Ottola Nesmith’s role as Old Laura Bellman in Boris Karloff’s Thriller episode called The Hungry Glass, where she is hideously painted up similarly to Jane looking like a fossilized doll. Jane’s makeup is exaggerated to the point of being grotesque. Here’s Ottola’s version of Laura Bellman.

“Oh, leave me alone won’t you, leave me alone with my mirrors!”

The great Ottola Nesmith (1882-1972).

There are old wounds, and an inability to release the past. Familial resentments with the sibling rivalry, incestuous undertones, a blatant exercise of sadomasochism, and of course the emotional torture that Jane puts Blanche through as well as Jane’s own self-delusion and spiraling downward into full-blown madness.

Throughout Baby Jane Aldrich uses zooms, close-ups for the point of view emphasis, and cross-cutting to create tension and suspense. One of the methods he used was called a shock edit, so we would go from seeing Blanche talking about how “alive” Jane used to be, instantly to Jane standing there listening at Blanche’s doorway. Blanche would be on the phone pleading with Dr Shelby and then pow! Jane is peering from the doorway.

Davis obviously had the more reaching characterization, to be able to balance the lines between acting bold and then regressing would be challenging in a way as not to let it become too farcical. Davis’s facial expressions, her sardonic smiling adds a level of uniqueness that no one else could have fit so perfectly, not even as incredible as Vivien Leigh was as Blanche Dubois in Elia Kazan’s A Street Car Named Desire(1951) the part of Jane Hudson was made for Bette Davis.

Crawford however had to play it straight. That is not to say that she didn’t add depth to Blanche Hudson, sister, invalid, and ultimately prisoner. Perhaps the contrast created a more tense atmosphere because of the extremes in the level of emotional output by both characters, and both actresses. I do wonder if Bette secretly enjoyed kicking Joan in the head and guts when she was down.

In fact during the whole time, of Blanche’s imprisonment, I still feel more pathos for Jane as a tragically pathetic figure than for Blanche’s invalidism and torture. I also felt sorry for the bird and the rat. I had a pet rat for several years, and she was a dear friend to me. Jane evokes more sympathy from me at least, maybe it’s that I love Bette Davis so much! Or perhaps Jane’s sad anger, made me feel something deeper than for the cold Blanche who although wheelchair-bound, seemed to be in command of herself at all times. Well except for the dying on the blanket thingy.

As I’ve discovered through reading several books about director Robert Aldrich I learned that he had a preoccupation with the “Hollywood” motion picture business, the actual art of filmmaking, its process, and the people who inhabit its tumultuous reputation.

Aldrich’s preoccupation with the enigma that is Hollywood, is even evident in his film The Big Knife(1955) starring Jack Palance. A film I’ll be covering later on as I will also be commenting similarly on Elia Kazan’s A Face In the Crowd with Andy Griffith as the charismatic Lonesome Rhodes the egomaniac whose mania as a showbiz prophet consumes himself and Patricia Neal. And Aldrich’s focus on Hollywood narrowly grazes on films like The Killing of Sister George (1968) through its BBC television, The Legend of Lylah Clare (1968), and of course, What Ever Happened To Baby Jane (1962) Collectively I think these films show Aldrich’s cynicism and ambivalence toward the film industry.

We can see the “Gothic” influences of Baby Jane in some of Aldrich’s later work. Just look at the styles of both Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte(1964) which again will be Part III & IV of this commentary and The Legend of Lylah Clare (1968) The characterizations are flush with a sort of delirium.

In Baby Jane as well as Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte Aldrich pushes the boundaries of perception, both ours and the main characters. We have to wonder if these films framed points of view for us as “spectators” are real or imagined. Where are the lines that separate the cognitive hallucinations from the visions of stark reality? Aldrich creates a symbiotic relationship between us and the protagonist/antagonist, and in the case of Baby Jane, it’s not necessarily for Blanche, as I’ve said for me the connection, the identification is actually with Jane.

Blanche’s passive-aggressive behavior betrays her guilt in retrospect so that in the end it’s no surprise when she reveals that she could be as dangerous, or prone to a fit of violence herself. She did in fact try to in her own words “crush” Jane.

This potential aggression and sociopathic tendency emerge once Blanche confesses about that fateful night. In this way, Blanche is every bit the monster, the murderous one who didn’t succeed, yet spends the next 30 years allowing the guilt to consume Jane causing whatever fragile identity and mental illness to brew because she robbed Jane of her life and of the truth.

Another observation, which I think is intentionally symbolical in the film, is that it is Blanche who is always dressed in either black or dark colors, the symbol of the femme fatale or evil figure, whereas it is Jane who is always dressed in baggy or billowy light or white clothes, the color of innocence. Perhaps this was a hint.

Hitchcock even employed the use of this cinematic device with Psycho, When at first Marian Crane (Janet Leigh) steals the money we see her dressed in a black bra and slip. But once she decides to go back and end her illicit affair with John Gavin, we see that she has transformed her look and is wearing the virginal white bra and slip. The use of color as an unspoken tool of language is as significant as the use of light and shadow to relate the narrative in film.

And although Jane was driven to kill Elvira, she did this in a hysterically regressed state of mind, that of a child, lashing out when feeling threatened. She probably wouldn’t have to stand trial, because she would be considered mentally incompetent to testify.

Baby Jane as well as Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte’s (1964) characters are Gothic women Archetypes who represent narcissism, the neurotic, the hysterical, the paranoid the delusional, the repressed, the emasculating mother, the regressive woman/child, and or the psychotic and the deviant sexual figure. And we lose our focus on how and why Blanche becomes an invalid as we become submerged in Jane’s systematic imprisonment of her sister.

We are drawn into the madness as the picture relates itself to us in a series of tactics strategized by Jane’s hysteria. Her distorted sense of reality and self-preservation in order to be able to keep the house that Blanche is trying to sell and commit Jane. And as brutal as Blanche’s entrapment becomes for us to witness, I still feel an exquisite empathy for the tragic and pathetically delusional Jane Hudson, an aged child star left with nothing and no one but her famous dependent sister Blanche and memories of a once lucrative career where she was at the center of the universe, and possibly sexually abused by her father.

In Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte(1964) Bette Davis‘ Charlotte is more obvious as the protagonist and less of a cipher with whom we align ourselves. While Charlotte is still a regressive victim, she is also an anti-hero that we are rooting for, despite her aura of instability.

For the 50s and 60s, melodramas consisting of plots about mental illness weren’t typically conventional, and a film as extremely grotesque as Baby Jane could be considered very disturbing. Even as groundbreaking as Hitchcock’s Psycho(1960)was, released the same year as Baby Jane. Psycho’s narrative veiled Norman Bates as a mild-mannered young man with an Oedipus complex. In Baby Jane, her flagrant derangement is glaring.

Perhaps films like Val Lewton’s Bedlam 1946, Anatole Litvak’s The Snake Pit 1948, and Sam Fuller’s Shock Corridor 1963 addressed the systemic institutional problems surrounding mental illness, but Aldrich’s films are very intimate ventures.

In Aldrich’s Autumn Leaves (1959) Crawford plays Millicent Wetherby a middle-aged woman who has no love in her life until she meets the very charismatic yet psychotic Burt Hanson, played Cliff Robertson. This is Aldrich’s first examination of the female psyche. Although it is Robertson’s character who is mentally ill, it’s Crawford’s character who has the conflict and struggles as she enables Hanson’s psychosis.

In The Killing of Sister George, (1968) Beryl Reid’s character June ‘George’ Buckridge must live a dual life because she is secretly a lesbian. What better example of “Other” is there, but to portray a homosexual in a film living in and acting of that era? Sister George who is cast as the cheerful nurse on the BBC soap opera must keep her fits of rage together when in real life, her world is coming apart. More so in the 60s, gays often appeared as either deranged, or suicidal, or were killed off by the plot. At any rate, they were not allowed to “exist” in society. I recently watched Radley Metzger’s The Alley Cats An iconic Sexploitation jaunt that succeeds visually cinematic-wise but fails the social/sexual responsibility to the content as it regresses the way it portrays the Lesbian protagonist in the film. In the end, the girl goes back to her physically abusive fiance and the beautiful Lesbian mistress is left being viewed as a pariah and a predatory deviant.

While what’s called Aldrich’s “Hollywood Morphology” films that blend the business of filmmaking and conflict like The Legend of Lylah Clare and Baby Jane do feature female protagonists as do Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte and The Killing of Sister George (1968) it does sort of seem that the women are merely iconic caricatures, epitomizing certain abnormal and deviant behavior depending on how you view them yourself.

Reid’s Sister George is a brutish alcoholic, irrational, possessive, and abusive rage- an alcoholic whose combustible wrath hurls barbs at anyone whom she views as threatening her domain. It’s her self-destructive behavior that becomes her undoing. Transforming her from initially being a formidable actress and the figure of respect to a solitary “mooing” shell of a middle-aged dyke, after wrecking the set of the soap opera in a fit, at the close of the film. (She’s been killed off on the show, but has been offered the part of a cow in a children’s animated series, thus the resigned mooing)

Peter Shelley brings out in his book, Grand Dame Guignol Cinema: “A History of Hag Cinema From Baby Jane to Mother” that if you look at the film titles themselves., Baby Jane, Sister George, Sweet Charlotte, and Aunt Alice in which the lead women are all defined by their first names using identifying adjectives it sets up an expectation for us of how the characters will project themselves.

In this way, I do assert that Aldrich “Otherizes” these women. Both Jane and Charlotte live on the perimeters of “normal” societal expectations. They are loners, outcasts, outliers, and renegades in that their fanaticism, serves to separate them from being “one of us.”

The concept “Other” is a term defined in the seminal work of Julia Kristeva who elaborates on Freud’s theories. She is a noted scholar and famous for her critical examination of Freud’s theory of “The Uncanny” and her essay on Abjection which is a very interesting read, but I digress as I am apt to do. Below are some excerpts from Kristeva’s writings on cultural theory and critical analysis which fit very well with and perhaps describe the dynamics of Jane’s psychosis.

Julia Kristeva here is her Wikipedia page.

Here is a great link about Freud’s The Uncanny by Horror Film History

http://www.horrorfilmhistory.com/index.php?pageID=childsp

Excerpt from Julia Kristeva’s essay Powers of Horror – An Essay on Abjection: translated by Leon S Roudiez

NEITHER SUBJECT NOR OBJECT

There looms, with abjection, one of those violent, dark revolts of being, directed against a threat that seems to emanate from an exorbitant outside or inside,ejected beyond the scope of the possible, the tolerable, the thinkable. It lies there quite close, but it cannot be assimilated. It beseeches worries and fascinates desire, which nevertheless, does not let itself be seduced.Apprehensive desire turns aside; sickened it rejects. A certainty protects it from the shameful- a certainty of which it is proud holds onto it. But simultaneously, just the same,that impetus, that spasm, that leap is drawn toward an elsewhere as tempting as it is condemned. Unflaggingly like an inescapable boomerang, a vortex of summons and repulsion places the one haunted by it literally beside himself.

The Abject is not an ob-ject facing me which I name or imagine, nor is it an ob-jest, an otherness ceaselessly fleeing in a systematic quest of desire. What is abject in not correlative providing me with someone or something else as support. Would allow me to be more less detached and autonomous. The Abject has only one quality of the object-that of being opposed to “I”. If the object, however through its opposition settles me with the fragile texture of a desire for meaning which as a matter of fact makes me ceaselessly and infinitely homologous to it, what is Abject on the contrary , the jettisoned “object” is radically excluded and draws me toward the place where meaning collapses, A certain “ego” that merged with it’s master a “superego”has flatly driven it away. It lies outside, beyond the set. and does not seem to agree to the latter’s rules of the game.

And yet from it’s place of banishment, the abject does not cease challenging it’s master. Without a sign to him/her it beseeches a discharge , a convulsion a crying out. To each ego it’s object , to each super ego it’s abject. It is not the white expanse or slack boredom of repression not the translations and transformations of desire that wrench bodies, nights and discourse, rather the brutish suffering that “I” puts up with sublime and devastated, for “I” deposits it to the father’s account.(I endure it, for I imagine that such is the desire of the other. A massive and sudden emergence of uncanniness, which familiar as it might have been in an opaque and forgotten life, now harries me as radically separate, loathsome. Not me. Not that. But not nothing either. A “something”that I do not recognize as a thing. A weight of meaninglessness about which there is nothing insignificant and which crushes me. On the edge of non-existence and hallucination, of reality that if I acknowledge it, annihilates me. There, abject and abjection are my safeguards. The primers of my culture.

AT THE LIMIT OF PRIMAL REPRESSION

If on account of the Other, a space becomes demarcated separating the abject from what will be a subject and it’s objects it is because a repression that one might call “primal” has been effected prior to the springing forth of the ego, of its objects and representations. The latter in turn as they depend on another repression, the “secondary” one,arrive only outside on an enigmatic foundation that has already been marked off;in return, in a phobic, obsessional, psychotic guise or more generally and in more imaginary fashion in the shape of abjection.Notifies us of the limits of the human universe.

Essentially Aldrich utilizes these Gothic Archetypes in his films where there is an ultimate interconnectedness of the “Other” theme and the madness stereotypes blended all together and concocted into one film.

Bette Davis and Joan Crawford ARE horror objects in Baby Jane. There is not much difference between an “object of desire” and an “object of horror” as far as the male gaze is concerned. It’s been referred to as the Monstrous Feminine.

In the chapter “When the woman looks” from The Dread of Difference the essay by Linda Williams -addresses this theme, here are a few excerpts:

“It is a truism of the horror genre that sexual interest resides most often in the “monster” and not the bland ostensible heroes who often prove powerless at the crucial moment”

M.G. – to me it brings to mind The Phantom of the Opera, Frankenstein, Dracula, Beauty and The Beast, King Kong, Creature from the Black Lagoon and so on.

Williams goes on to describe:

“Clearly the monster’s power is one of sexual difference from the normal male…it may very well be then that the power and potency of the monster body in many classic horror films-should not be interpreted as an eruption of the normally repressed animal sexuality of the civilized male(the monster as double for the male viewer and characters in films) but as the feared power and potency of a different kind of sexuality (the monster as double for the women).”

“As we have seen one result of this equation seems to be the difference between the look of horror of the man and of the woman. The male look expresses conventional fear at that which differs from itself.The female look-a look given preeminent position in the horror film-shares the male fear of the monster’s freakishness but also recognizes the sense in which this freakishness is similar to her own difference. For she too has been constituted as an exhibitionist -object by the desiring look of the male. So there is not much difference between the object of desire and an object of horror.”

“In one brand of horror film this difference may simply lie in the age of it’s female stars.The Bette Davis’s and Joan Crawfords considered too old to continue to as spectacle – objects nevertheless persevere as “horror objects”in films like Baby Jane and Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte. The strange sympathy and affinity that often develops between the monster and the girl may thus be less an expression of sexual desire (as in King Kong, Beauty and The Beast) and more of a flash of sympathetic identification.”

These actresses were on exhibition for the Hollywood machine years earlier in films as objects of desirability. Now as older women they have been cast in a movie of stylized freakery, by this, they have been transformed into objects of grotesque femininity. Jane blurs the lines between her childhood and her womanhood even with her makeup and childlike clothes adding a psycho-sexual aspect to the melodrama and Neo-Gothic style.

Norma Kotch won an Oscar for her costume design on Baby Jane, and Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte as well as Aldrich’s The Flight Of The Phoenix (1965)

Also characteristic of the two Gothic films Baby Jane and Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte, Aldrich inhibits the environment to remain mostly in a house, unlike other of his films, where the landscape changes and are filmed with vast exteriors. The Dirty Dozen, Flight of the Phoenix for example.

The house also functions as the imprisonment, the captor. Therefore the mansion in which the characters of the films live is not just simply a setting. They have their own specific significance to add to the narrative. The house is an Italianate villa located in Hancock Park, which was once a fashionable district of Hollywood. It also reflects the past.

It is as much a personification, a character, as the actors themselves. As it underlines the atmosphere of alienation and delusion. It not only creates another layer of tension and dread but gives us a classification of the surroundings for the characters to act out the dynamics of their pathology and depraved rationalities.

It brings to mind Eleanor in The Haunting (1963) Hill House had its very own presence, an identity that Eleanor felt a kindred connection to, the constant inner monologues( god help me) to belong there, much to her downfall. The way Robert Wise filmed the odd angles to give Hill House its own distorted persona was key to creating the atmosphere of a sick, threatening house. Richard Johnson’s Dr. Markway and Julie Harris’s Eleanor refer to it as “adding up to one big distortion as a whole” and that the house was “born bad.”

Robert Wise’s film is probably my favorite next to Rosemary’s Baby. When I finally do sit down and write my thoughts about these 2 films plus my overview of Val Lewton’s work, I’ll have to break it up into 8 parts over the course of several weeks and you’ll all hate my long-winded diatribes by then.

Again, houses like these have been referred to in particular by Freud in his essay “The Uncanny” as “primal areas”, actually a substitute for the womb where individuals wrestle with their inner conflicts. So add a demented woman who’s already delusional, and put her in a claustrophobic environment, shut her off from reality and authentic contact with the outside world, and the madness festers.

Even though Aldrich has used women as the protagonist/antagonist he paints these women as “objects” usually as unattractive, morally corrupt or treacherous, or in fact mentally ill. Just to refer back to The Killing Of Sister George, with Beryl Reid (loved her in Psychomania -1973) as the aging soap opera star who is a not-so-closeted lesbian. One could say that Aldrich characterizes her as the stereotypical butch who is more masculine than most of the men in the film. In addition, her behavior is demonstrated as being repulsive at times, and considered deviant by some. There’s an over-the-top macho bravado and domination over her much younger lover, Alice “Childi” played by Suzanna York. The scene where George makes Childi eat her cigar slowly, provocatively chewing it until she ruins the ritual for George as she starts to look like she’s aroused by the act and not the intended purpose of demeaning her is pretty powerful stuff. Coral Browne is fantastic as the subtly predatory woman who steals Childi away from George. Browne and Vincent Price were a very devoted husband and wife.

But back to Aldrich and his use of objectifying his female characters as monstrous.

Of course the pathetic Baby Jane, then Davis plays regressive recluse Charlotte in Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte and in the Legend of Lylah Clare with Kim Novak, she is also a performer who begins a slow descent into delusion. These women are portrayed as deviating or deranged. Sister George and Lylah Claire are performers who retreat from the male-dominated world and turn to bisexual behavior or Lesbianism as an alternative. Although it seems for Aldrich, that the gender of his characters is less significant than their actual strife and conflict, and how it plays out.

Aldrich partnered with Joseph E Levin to purchase the rights to the British writer John Farell’s Hollywood horror book in 1961. It’s has been noted in interviews with Aldrich that his working relationship was already very good with Crawford having worked with her on Autumn Leaves (1959). However, with Bette Davis, he had to do a little more convincing. Eventually, she was on board with the project.

By the time Aldrich bought out Levine the story price had gone from $10,000 to $85,000 and no one seemed interested. But Aldrich relates in an interview that “Eliot Hyman at Seven Arts read the script, studied the budget and told him candidly: “I think it will make a fabulous movie, but I’m going to make very tough terms because it’s a high-risk venture.”

So it was Aldrich’s persistence and his faith in the project that made Davis enthusiastic about the film. Crawford had already expressed a desire to work with Bette Davis in a film. For Bette to take on such an unattractive role was pretty gutsy for her.

Baby Jane grossed $4 million in the U.S., Canada, and worldwide, with Aldrich having to give 25 percent to Warner for distribution and then shares of 15% to Crawford and 10% to Davis.

Of course, both actresses went on to do similar personifications of the iconic hag. Joan did William Castle’s Straight Jacket (1964) in direct response to Hitchcock’s success with Psycho (1960). The psychological thriller using madness was emerging. Although as I’ve previously stated Crawford was the protagonist and peripheral accomplice to Cliff Robertson’s insanity in Autumn Leaves, it is said there are similarities in tone from that picture to other of Aldrich’s later hag cinema works. I’ll have to revisit Autumn Leaves as I watched it a few years ago.

There was also Crawford’s I Saw What You Did (1965) Trog (1970), Berserk (1967), and her vignette on the Pilot movie for Rod Serling”s Night Gallery (1969) television series.

Crawford plays in the second story, a rich, heartless woman who has been blind since birth. Surrounded by opulence, statues and paintings, and trappings of the very rich. She blackmails an aspiring surgeon and a man in debt to his bookie who desperately needs money to give her a pair of eyes that will allow her to see for the first time – even though it’ll only last for half the day -Ultimately the plan backfires on her.

Bette went on to do hag/crone-type characters such as Dead Ringer (1964) The Nanny (1965) The Anniversary (1968) “The widow fortune” in Tom Tryon’s The Dark Secret of Harvest Home (1978) Watcher in The Woods (1980) Jimmy Sangster’s Scream Pretty Peggy (1973), and though a minor role in terms of her participation, she did contribute an element of the grotesque in the scene where she is sweating, writhing, bloated and frightened into a heart attack in Dan Curtis‘ Burnt Offerings (1976) The image of the long-legged hearse driver in all black and dark shades, rolling the coffin through the bedroom door is a scene I will not soon forget.

For me, Baby Jane and Hush Hush ARE the two benchmark Hag/Spinster Gothic Horror Melodramas that immediately come to my mind, although there was a rash of films in this sub-genre that fit the mold, starring actresses that inhabited similar personas. The success of Aldrich’s 2 films opened the way for older actresses to get their rage on as it were! Just to mention a few like Gloria Grahame in Blood and Lace (1971) Agnes Moorehead in Dear Dead Delilah (1972), Tallulah Bankhead in Die Die My Darling (1965) Piper Laurie in Ruby and Carrie Kim Stanley in Seance On a Wet Afternoon (1964) Barbara Stanwyck in The Night Walker (1964) Viveca Lindfors Bell From Hell (1973) Shelley Winters in the variation on the Hansel and Gretel fairy tale Who Slew Auntie Roo? and Ruth Roman in A Knife for the Ladies (1974) and one of my favorites by Curtis Harrington What’s the Matter With Helen (1971) starring once again the great Shelley Winters and Debbie Reynolds. Geraldine Page in What Ever Happened to Aunt Alice (1969) and Rosemary Murphy In You’ll Like My Mother. And Stella Stevens in The Mad Room. Debrah Kerr in The Innocents and Olivia De Haviland in Lady in A Cage.

Even Dame May Whitty in Night Must Fall, and Teddy Bear’s older wife Margaret Lockwood in Cast A Dark Shadow. Gloria Swanson in Sunset Boulevard Ruth Gordon as Minnie Castavet in Rosemary’s Baby(1968) and Lily Palmer in The House That Screamed (1969) and even Simone Signoret in Curtis Harrington’s Games.

In the 1960s, telescoped through the male perspective, the Hollywood actress was transformed into the regressive Hag, succumbing to the despair of loneliness and clouded by their inability to judge whether they might be in danger, existing in a dwelling place of a sort of euphoric delusion that has befallen them. Ultimately they are either put at risk, falling victim to murder or becoming murderers themselves.

What Ever Happened To Baby Jane has been adopted by the gay community and incorporated into many drag queen shows. The DVD release has a special commentary by John Epperson (Lypsinka) The iconic histrionic characters seem to have had a major influence in the gay cabaret society, which adds another level to its cult status, although, in some regards, it trademarks these films with a “campy” vibe and perhaps redirects the attention away from being considered serious pieces of work amongst film critics and film enthusiasts. I think both can occupy the same space and still exist as relevant.

What’s most fabulous about the film is that it has both Bette and Joan, which gives it such a dynamic double billing. The film really was a seminal work because nothing quite like it had been done earlier. Films like Sunset Boulevard (1950) and Autumn Leaves (1959) set some groundwork for older actresses to wax crazy dramatic in film. But ultimately the pot boiled over with Baby Jane and Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte.

Aldrich’s Mise en scène is often violent. Serving Blanche at first the bird on the plate, and then the rat, is repulsive. Jane tying Blanche to the bed is perversely erotic as they are sisters. Jane kicking Blanche in the head and guts, while she’s on the ground, is purely brutal. And the culmination of the ultimate Grande Guignol, Elvira’s murder by hammer.

Again I ask the question, just to put it out there, Is there a pattern of misogyny in Aldrich’s work or in fact the writers he is adapting his work from? Looking over collectively the films that depict his women in sadistic and demeaning ways, some could make a case for it.

There’s evidence of this in The Big Knife with Jack Palance and written by Clifford Odets the element of misogyny creates an environment where it seems the female characters are there merely to be devalued by men. With Aldrich’s films women screaming becomes a recurring motif and we hear sentiments like “Dames are worse than flies”

Once again from Peter Shelley’s book, he tells us that in Aldrich’s film Kiss Me Deadly (1955) “there are references to Lot’s Wife, Medusa, and Pandora in a pulp narrative that present women as victims, whores, murderesses or Viragos.”

The term Virago refers to a woman who is domineering and bad-tempered with masculine strength or spirit. Even perhaps considered a warrior. Its origins lie in the mythology of Adam and Eve. It was the name given to Eve by Adam originally pronounced Vulgate from the Latin “heroic woman, the female warrior”

EVE

MEDUSA

and of course, NORMA DESMOND.

Writer Mickey Spillane channels his idea that women are the “incomplete sex” using Christina Baily as the vehicle for this sentiment and ultimately a deceitful woman opens up Pandora’s Box by setting off an apocalyptic nuclear explosion that burns her to a crisp and poisons all of Los Angeles. Here is the theme of women as annihilators. The Monstrous Feminine. The Devouring mother, she’ll take your penis. Destroyer of mankind. The fall from grace in the Garden of Eden all over again. Although we do not see the violence on the screen, Christina Baily is tortured with a pair of pliers in Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly.

Baby Jane was not an easy sell, even with the double billing, both the actress’s box office draw had diminished by then. Later on, Aldrich said that the problem with Jane was that “the topic was perceived as controversial and not a built-in moneymaker which would alienate portions of the public”

Jack Warner was quoted as saying he “Wouldn’t give a plug nickel for either one of those old broads” As far as I’m concerned Warner was an asshole!

But Aldrich got Seven Arts Pictures curious about the film and so Warner Bros agreed to distribute the film but didn’t allow it to be made on the Warner lot.

Notice the doll’s hair in the poster is black, yet the Baby Jane doll has blond ringlets!

TAGLINE ADS READ:

“Sister sister oh so fair why is there blood all over your hair”‘ the poster included 5 points or things you should know about this motion picture before you buy a ticket” They are

1) If you’re a long-standing fan of Miss Davis and Miss Crawford, we warn you this is quite unlike anything they’ve ever done.

2) You are urged to see it from the beginning

3)Be prepared for the macabre and the terrifying

4)We ask your pledge to keep the shocking climax a secret

5) When the tension begins to build remember it’s just a movie

The film premiered on October 26, 1962. and released on Halloween in 1962. Davis was nominated for the Best Actress Academy Award and Buono for the Best Supporting Academy Award. The film was remade for TV in 1991 starring the real-life Redgrave sisters, Lyn and Vanessa. I’ll stick with the original.

SOME REVIEWS

“Joan Crawford and Bette Davis make a couple of formidable freaks but this unique conjunction of the 2 one time top ranking stars does not afford either the opportunity to do more than wear grotesque costumes and makeup to look like witches and chew the scenery to shreds” -Bosley Crowther, The New York Times, November 7 1962

“In what may well be the year’s scariest, funniest, and most sophisticated chiller, Davis gives a performance that cannot be called great acting but is certainly Grande Guignol. And Joan effectively plays the bitch to Bette’s witch…Aldrich knows just when to play his gargoyles for giggles” -TIME, November 23, 1962

Sources:

Julia Kristeva excerpts from the essay on Abjection Powers of Horror and Essay on Abjection.

What Ever Happened To Robert Aldrich? Alain Silver & James Ursini

Grande Dame Guignol Cinema-A History of Hag Cinema From Baby Jane to Mother-Peter Shelley

The Dread of Difference -by Linda Williams-essay-When The Woman Looks

Dear Monster Girl,

I was thrilled to find your awesome Horror Movie History site! Your posts are so informative and very well written ! I enjoyed reading several of them and will come back again to read more about all of the spooky movies I have loved since childhood! The background info you gave about the movies was particularly interesting, as I did not know a lot of the historical movie trivia that you have researched and written about! I learned something new about a few of the movies I am a great fan of ! I appreciate all of the long hours and hard work you have put into these incredible posts—-Keep up the great work!

Now I need to ask you a favor!!!

I am a mixed media artist and I am creating an altered art mini-book on “Whatever Happened To Baby Jane?” for a entry into the Altered Bits E-zine that will be published in April!

The theme I am working with is “Notorious” and the first thing I thought of when I read about the theme was the two most “notorious actressess ” of the day—-Bette Davis and Joan Crawford !

“Whatever Happened To Baby Jane” has been a favorite movie of mine for years and so I thought about creating a altered art book from the photo clips and quotes from the movie and combining that along with a “behind the scenes” look from quotes and images taken from the great Davis/Crawford rivalry!

I found some pictures, movie clips, and quotes from the movie and the actressess in Wikipedia Commons but not enough to really give my art work the exact definition of “Notorious” that I wanted to reflect in the altered images I have created in the mini-book!

I wanted to ask your permission for the use of several images that I saw in this post that I would dearly love to use for my E-zine entry! Do you allow others to use any of your images for art work? I would most definately give you credit for the pictures I used–if fact–that is a stipulation of the Altered Bits E-zine! We must ask permission for any images used and we must give credit to all sources from where we got the images from that was used in our at work!

We are not allowed to use anything that might infringe on someone’s copyright ! I didn’t know if your images were in public domain or if you have a copyright on them but I did notice that at the end of the post you show the option to share this post by printing it or e-mailing it! So I am hoping that means that your intent is for people to use them for personal or entertainment purposes but not for peronal gain or for profit of any kind! I have a web site that I offer vintage images on and my rule is for the images to be used for personal but not profitable means! In other words, they cannot take the images I offer and create collage sheets from them to sale for their own profit! They can use them for their own personal art work and sale that art work because the image they used from my site has been altered from the original image I posted!

I do not receive any payment whatsoever for this art entry into the Altered Bits E-zine! This is for personal participation only–not for income!

My deadline was today but I can get an extension of 2-3 more days to turn everything in so if you could e-mail me back and let me know if I can use a few of your movie clips, 8 to be exact, for my art work, I would be so grateful!

If you need to check out the web site that publishes the E-zine–

this is the web address:

http://www.alteredbits.com

I will also post this altered art book on my web site with a special link to you if you give me permission to use your images for my art work! Anytime I use a image that I have altered for art work that I enter into competitons or contests, I always get permission first, give credit to that person and their web site/shop where I got the image from, and also add a link in a post for others who would also like to visit the site!

Hope to hear from you really soon!

Thank you so much,

Kym Decker

kymdecker@charter.net

Other sites I have:

http://freetrinketstreasures.blogspot.com

http://missannesvinatgeart.blogspot.com

http://vaerieenchantedfaeries.blogspot.com

You’re a dear for putting up with my long windedness. Of course you can dabble with any of my images. The project sounds great! Thanks for checking out my thoughts here at the drive in, and do stay in touch.

Cheers

Joey aka Monster Girl

ephemera.jo@gmail.com

Awesome article.