The Killers (1946) is the quintessential existentialist film. Based on Ernest Hemingway’s 1920s short story as he was immersed in the pre-war existentialism of that time period, which fostered tales of crimes and violence. As the two French critics Raymond Borde and Etienne Chaumeton remark in their fantastic read and seminal work A Panorama of American Film Noir 1941-153 the killer’s gunmen walking into the diner in Brentwood N.J. and begin complaining about the menu predates the dark Absurdism of the existential movement of playwrights like Harold Pinter and Samuel Beckett.

It reminds me of how great directors like Quentin Tarantino pay homage to films like The Killers in Pulp Fiction, or the work of Samuel Fuller who didn’t hold back on the vicious realism that was groundbreaking in its day.

According to the Electric Sheep blog, “The first twelve minutes of The Killers (1946) is a faithful (almost word for word) adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s much-anthologized short story. Two hit men enter a diner (shot to look like Edward Hopper’s painting Nighthawks – itself apparently inspired by Hemingway’s story) typical Hemingway heroic fatalism.”

Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946): Brutal Noir- The First 12 Killer Minutes!

The Killers (1946) the original version scripted by Hemingway himself, was produced by Mark Hellinger (The Naked City, Brute Force, and The Two Mrs Carrolls– 3 of my favorite films,) and once again boldly directed by the great Robert Siodmak. With the rise of Nazism Siodmak left Germany for Paris and then for Hollywood. He’s singularly responsible for a great deal of the noir films that are so memorable.

In my opinion, Siodmak’s film is a meatier piece of work that rendered a more brutal impression than the 1964 version directed by Don Siegel.

Perhaps due to its more neo-gangster noir style, it gave it a liminal and evocative intensity. Siodmak’s Killers has a more violently surreal tone, than the stylishly slick and richly colorful pulpy Siegel version. The effective black-and-white environment of the 1946 Killers once again sets the stage for the players to live in a world that is condemned by shadow. While I love Siegel’s version, it does seem brighter and the world more aired out than usual frames of noir desolation.

Although I’m a huge fan of Angie Dickenson and she was incredibly lush and provocative in the role of Sheila, Ava Gardner’s Kitty Collins was more subtly carnal as the temptress who becomes Swede’s downfall. Siodmak’s version gives us the noir police investigation, there is pervasive Machiavellian cruelty, and the characters have more stratum to their personas. John Cassavetes is more icy while Burt Lancaster’s Swede is a very sympathetic yet imperfect man, that fatalistic heroism.

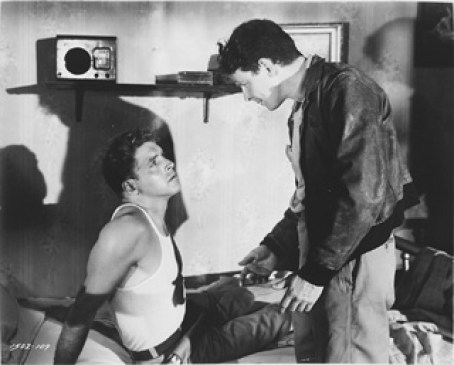

Burt Lancaster plays Ole “Swede” Andersen ex-boxer and con, Ava Gardner is Kitty Collins, Edmond O’Brien is Jim Reardon insurance investigator, Albert Dekker is Big Jim Colfax (Dr. Cyclops) criminal mastermind and Virginia Christine is Lily Harmon Lubinsky (she cameos in the ’64 version as the blind secretary).

Sam Levene is Lt. Sam Lubinsky Swede’s old childhood friend Charles McGraw( The Narrow Margin) is Al the killer and William Conrad (Cannon tv series)is Max the other killer. The Killers also casts Jeff Corey as “Blinky” Franklin (The Outer Limits O.B.I.T.episode) one of Big Jim’s criminal lackeys with a “monkey on his back” implying that he has a drug addiction. And Vince Barnett as Swede’s devoted and world-weary petty thief Charleston.

The film opens with Miklos Rozsa’s ominous brassy jazz score that later becomes the killer’s motif, as the two men drive into a small American town, anywhere USA, we see them from behind in the darkest black silhouette in the car. Then a long view of them walking onto the scene still surrounded in shadow, we know they are trouble. The opening scene of The Killers is perhaps one of the most powerfully ferocious I’ve seen from a 1940s film.

The two men enter Henry’s Diner William Conrad’s Max and McGraw’s Al, are The Killers, who begin to psychologically torture George who works the counter, and Nick Adams the boy at the end of the counter. They exude an obnoxious egotism. A cruel anti-social spirit as they barrage the men in the diner with verbal assaults, having a somewhat perverse quality that begins with the menu.

George: What’ll it be, gentlemen?

Max: I don’t know. Whatta you want to eat, Al?

Al: I don’t know what I want to eat.

Max: I’ll have the roast pork tenderloin with apple sauce and mashed potatoes.

George: That’s not ready yet.

Max: Then what’s it on the card for?

George: Well, that’s on the dinner. You can have that at six o’clock. That clock is ten minutes fast. The dinner isn’t ready yet.

Max: Never mind the clock. What have you got to eat?

George: Well, I can give you any kind of sandwiches: bacon and eggs, liver and bacon, ham and eggs, steak…

Al: I’ll have the chicken croquettes with the cream sauce and the green peas and the mashed potatoes.

Max: Everything we want is on the dinner.

They continue to harass George, asking for alcohol, “Al: You got anything to drink? George tells them “I can give you beer, soda, or ginger ale. Al: I said you got anything to drink?” George submits a quiet “no.” Max says “This is a hot town, whatta you call it?“George“Brentwood” Al turns to Max “You ever hear of Brentwood?” Max shakes his head no and then Al asks George “What do you do for nights?”Max takes in a deep breath and groans out “They eat for dinner, they all come here and eat The Big Dinner” George looks downward and murmurs “That’s right” and Al says

“You’re a pretty bright boy aren’t you”, meanwhile George is a grown middle-aged man. The term “boy” is designed to demean him. George mutters “sure” and Al snaps back “Well you’re not!”

Al now shouts to the young man at the end of the counter “Hey you what’s your name?” he looks earnestly at Al and says “Adams, Nick Adams.” Al says, “Another bright boy.” There is an emerging sadism at work here, almost subconsciously homophobic/homoerotic, in the way they are using the terminology of “boy” working to subvert these bystanders’ manhood. Max says, “Town’s full of bright boys”

The cook comes out from the kitchen bringing the plates of ” one ham and one bacon” George starts to serve the men the food and asks “Which one is yours?“Al says “Don’t you remember bright boy?” the continued use of this phrase truly begins to flay the layers of our nerve endings. George starts laughing and Max says “What are you laughing at?” “nothing” “You see something funny?” “no” “Then don’t laugh” “Alright” Again Max says, ” He thinks it’s alright,” Al says “Oh, he’s a thinker” Here we see the anti-social backlash to an intellectual society that would perceive them as outcasts. The term “thinker” is used pejoratively as is “boy.” This is where the film begins to break the molds of the Hollywood window dressing of a civilized society when two intruders trespass on an ordinarily quiet community and shatter its sense of security. It is the death of humanism in film language.

Max and Al proceed to tie up Nick Adams and the cook in the kitchen. They further taunt George who asks “What’s this all about?” Max “I’ll tell ya what’s gonna happen, we’re gonna kill a Swede, you know big Swede, works over at the filling station” he lights a cigarette. George says, “You mean Pete Lund?” As Max takes the cigarette out of his mouth the smoke enervates in George’s face, “If that’s what he calls himself’, comes in every night at 6 o’clock don’t he?” Georges asks “What are you gonna kill him for? what did Pete Lund ever do to you?” Max replies,” he never had a chance to do anything to us he never even seen us.” The conversation is so matter-of-fact that it’s almost chillingly absurd. Again George asks, “What are you gonna kill him for?” and Max smirks “We’re killing him for a friend.” Al pokes his head in from the sliding panel window to the kitchen “Shut up you talk too much” but Max says ” I gotta keep bright boy amused don’t I?”

Once the killers believe what George tells them, that Swede isn’t coming into the diner for his supper because it’s passed 6 pm, they go to Swede’s boarding house. George unties the two men in the kitchen who have been bound up with dish rags, and Nick jumps over fences trying to head off the killers and warn Swede that they’re coming for him. Nick bursts into Swede’s room.

At first, we only see the obscured figure of a man lying on his bed, only from the neck down to his feet. We do not yet see the figure clearly. Swede is framed in shadow. Nick tells him about the men at Henry’s Diner, they were going to shoot him when he came in for supper.”George thought I oughta come over and tell ya” Out of breath Nick is panting, and we still only hear Lancaster’s substantial voice in a whispering tone “There’s nothing I can do about it,” Nick says “Don’t you even wanna know what they’re like?” “I don’t wanna know what they’re like, thanks for coming” Don’t you wanna go and see the police?” “No that wouldn’t do any good,” Swede tells Nick he’s sick of running and “I did something wrong (pause) once, thanks for coming” he ends very solemnly. Nick leaves. The last words we hear Swede utter are “Charleston was right, Charleston was right.”

Now we see Swede’s face just staring and waiting. Sitting up, as the killers come bursting into the room, blasts of light from the gun spray, we are left looking at Swede’s hand lying limp against the side of the bed, surrounded in shadow once again, he is dead.

The Killers relies a lot on the noir mechanism of the flashback. At times there are flashbacks within flashbacks.

We’re now at the police station with Nick and Sam the cook giving their statements. We see a silk scarf with harps among his effects. Swede left a death benefit life insurance policy for $2,500 that goes to a woman in Atlantic City. The case is now being investigated by an insurance detective for the Atlantic Casualty and Insurance Company. Edmond O’Brien plays Reardon, who refuses to drop the case even after his boss insists that it’s not financially worth the company’s time. But Reardon wants to know what happened to this man who had “8 slugs in him, nearly tore him in half.”

Reardon goes to the hotel in Atlantic City and talks to the old chambermaid, Queenie, who is the beneficiary of Swede’s death benefit. She tells Reardon that at least he could be buried in consecrated ground and Reardon asked why she thought it was a suicide.

Queenie tells him in flashback how she was working that night and came into Swede’s room to clean, and he was visibly disturbed, smashing and stomping the furniture crying out “She’s gone, she’s gone!” Queenie asks “Who’s gone, mister?” He picks up a chair and breaks the window and tries to jump out, but Queenie grabs him and tells him” For the sake of God, you’ll burn in hell for all time” and stops him from killing himself. The death benefit was his way of saying thanks for her kindness.

Reardon embarks on a journey to get the bell to ring in his head, about why the green silk handkerchief with the golden harps is on the tip of his mind. His boss says that claims are piling up and he’s off running around with a 2 for a nickel shooting, but Reardon wants to know why 2 professionals put the blast on a filling station attendant, a nobody. He also notices his hands, scarring which indicates that Swede had been a boxer at one time.

He meets up with Swede’s old boyhood friend from the 12th ward in Philly. Lt Sam Lubinsky who is now married to Swede’s one-time girlfriend Lily played by the young and ever-present character actress Virginia Christine who was also in The Killer Is Loose. In The Killers, she is absolutely beautiful as the “nice girl” playing opposite Ava Garner’s femme fatale role as Kitty. Sam joined the police force and Ole Swede started fighting professionally. They always kept in touch, but “when you’re a copper, you’re a copper” and eventually after taking a savage beating in the ring, Swede breaks his knuckles beyond repair and has to stop boxing. Sam winds up putting ” the pinch” on his friend Ole later on.

In a flashback, we see Lily and Swede at a party thrown at a swanky hotel by Jake, one of Big Jim Colfax’s men. Lily doesn’t like Jake, he’s got mean eyes. Swede sees Kitty for the first time sitting at a piano. Swede is mesmerized by Kitty. The women share competitive glances. Kitty says, “Jake tells me you’re a fighter,” he says “Do you like the fights?” Kitty says “I hate brutality Mr. Anderson the idea of 2 men beating each other to a pulp makes me ill.” Lily tells Kitty that she’s seen all of Swede’s fights, but Kitty comes back with “Oh really, I couldn’t bare to see the man I care about hurt” At that point Lily is finished once Swede remarks how beautiful Kitty is Lily leaves the party.

Lt. Lubinsky tells Reardon that “It seems like I was always in there when he was losing, ever see him fight? He took a lot of punishment.”

Ole’s manager leaves Swede after he isn’t any good as a money-making fighter anymore since the bones in his hand are crushed. It’s why he didn’t use his right hand to fight the night he lost the bout to Tiger Lewis. That night his manager says “No use hanging around here, never did like wakes”

In a flashback within a flashback, Ole starts dating Kitty Collins, Big Jim’s girl. Evidently, she shoplifts a diamond pin, Reardon recognizes it as she’s wearing it at a table sitting with a group of thugs who work for Big Jim Colfax. She drops it into a plate of soup, but Reardon stops the waiter, fishes it out, and rinses it off in a cup of coffee then tries to take Kitty in, but then “Ole” Swede walks in and winds up taking the rap for her spending 3 years in jail for Kitty’s robbery then he gets released for good behavior.

Kitty’s given him this green silk scarf with golden harps of hers, which he strokes in jail. Swede has a cellmate and friend in a man named Charleston, a petty larceny crook and old-time hoodlum who bonds with Swede while in prison. Charleston brings up Jupiter one night. He liked to look at the stars after lights out, he knew their names because he got a book from the prison library.

“You can’t learn any better about stars than by staring” Swede and Charleston stares out the window at the stars, while Swede is stroking the silk scarf Kitty gave him. He asks Charleston if he knows what “harp” means. He says “Yeah, angels play ’em” “They mean Irish, Kitty gave me this scarf.” But Kitty hasn’t come to see Swede once while he’s in prison for the robbery she pulled. Swede asks Charleston to look up Kitty when he gets out because he’s worried about her. But Charleston knows she’s not sick or in trouble. Swede is too much in love to see it.

Later on, Charleston relates to Reardon at a pool hall where he was told to bring Swede on the day after his release from jail because Big Jim is planning a “big set-up.” Also in the room is a thug named Dumb Dumb and Blinky Franklin. Charleston opts out, he only wants easy pickings at his age he’s spent half his life in stir, but Swede seeing Kitty in the room, still Big Jim’s girl, says he’s in. Kitty becomes Swede’s mistress again. We see the glances between the two, and Swede knocks Jim down when he tries to hit Kitty. The two men swear that after the heist, they will even up the score with each other.

The last thing Charleston says to Swede before he leaves the room is “Want a word of advice? stop listening to golden harps, they’ll land you in a lot of trouble.” We now know what Swede meant by his last words. Charleston leaves the room. Closing the door, hoping Swede will follow, but ” he never showed up, and I never seen the Swede again” We see the character Charleston in flashback standing outside the door. Framed by the shot making the door a principal moment in the film. Charleston stared at the door waiting, looking trapped and small. The door symbolizes the unknown and what lies behind or ahead.

Back at Atlantic Casualty and Insurance Co. Reardon tells his boss the “bell rang” he remembered hearing about it in relationship to a big caper that was pulled on July 20th, 1940 at The Prentiss Hat Company. Armed gunmen got away with a quarter of a million of Atlantic’s money. One of the robbers was seen wearing a green scarf with golden harps wrapped around his face like a bandit. Swede was one of the people involved in the heist. Now hiding out under an assumed name, and working at a filling station supposedly hiding all the loot from the Hat Company heist, taken away from the other members of the gang. Who sent the killers to assassinate Swede and did Kitty Collins sign his death warrant?

The Killers, details double crosses of all double-crosses, as ‘the killers’ go to the sleepy town of Brentwood to even a score with Swede, who didn’t take Charleston’s advice and stops listening to golden harps. In noir films, there is often a fetishistic quality to an item or action. I think the scarf is a sexual symbol of Kitty for Swede. It bares her scent, it was a token of her sexuality being made of “real silk” as if her skin. the idea of touching something golden. The scarf acts as a surrogate for Kitty’s body, as he strokes it in place of the real thing.

The 1946 The Killers is one of my favorite noirs, maybe my favorite of all. It’s got the most convoluted storyline of any of them but that makes it all the more fascinating. Also, it’s a rare case of a gimmick,–flashbacks within flashbacks–that actually works, and makes the film even more compelling.

Your description of the diner scene is as good as I’ve ever read. Good work, Joey! The first ten minutes are, arguably, cinematically and, especially, as to writing, the best in the film. The drive into the Brentwood as the credits run, the Rozsa score, makes the film start off in a totally modern way that’s fresh even today. That’s sharp on what may be the homophobia of the killers. McGraw and Conrad are nothing short of,–is there a better word?–magnificent. The other actors in the scene are just fine. The actual approach to the diner itself as well as its interior is suggestive of the paintings of Edward Hopper, and which even I noticed when I first saw the movie at the tender age of eighteen.

As to the killers being homophobic,–not that George, Nick or the cook come off as in any sense gay–they are treated that way by the city slickers Al and Max. As I’ve seen the film several times it has occurred to me that the killers may actually be gay, butch variety, who view all non-macho men are fem-potential boytoys whom they can use (and maybe abuse) sexually. Their verbal abuse of the people in the diner is extreme even by mob standards. Al and Max are likely freelancers, not Mafia hire anyway, which makes them even more dangerous, as they have no “code”. Since they’ve come to Brentwood (New Jersey, btw) to “drill” the Swede, well, the word drill has many connotations. They appear to be on a “drilling spree” that night, which spills over into their behavior toward the diner folk, who’ve done them no harm. There may indeed be a gay subtext to the killers themselves, who are always together, are never shown accompanied by women, which would be irrelevant anyway but may also be a “signal”: sadistic gay hitmen. And why not?

The movie is fascinating and labyrinthine in its plotting, with the robbery scene perfectly times. There are memorable supporting performances by Vince Barnett (Charleston), Jeff Corey (the dying junkie,–talk about modern!) and, especially, Jack Lambert as the troublemaker Dum Dum, who’s not actually so much dumb as a loose cannon. Albert Dekker makes a magisterial Colfax, Ava Gardner a stunning Kitty.

My favorite “action scene” in the film is in the bar at the end, when Al and Max arrive, to the tune later used on Dragnet, accelerated as they move down the bar; then the boogie-woogie piano kicks in, we spot Lubinsky, and the killers move toward Reardon and Kitty to the pulsating score now nearly drowned out by the piano music, and at last the climactic shootout, with Al and Max now the killed, no longer the killers. In the end they get “drilled” just like the Swede, only they didn’t see it coming.

I can’t praise this film highly enough. Woody Bredell’s camerawork was Oscar-worthy, as was the script, the art direction, the music and Robert Siodmak’s directing, but there’s no way it was going to beat out the far more timely The Best Years Of Our Lives at the Academy Awards. In my opinion the real best picture of the year was Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, which I rate a notch higher than The Killers, but not by all that much. The Killers actually has a few things in common with the Capra picture, including multiple flashbacks, a leading character with suicidal tendencies, and repetition of images and scenes, a well rounded aspect that for a cineaste is extremely satisfying in itself. They’re both classics, one yin, the other yang. The Killers could almost be retitled It’s a Terrible Life.

Thanks for the review, Joey

Nice comprehensive article and some great photos on one of my favorites.